Thick descriptions

One Man’s Meat is Another Man’s Poison: Meat, Feeding and Animal Subjectivity in Zoological Gardens

By Kees Müller

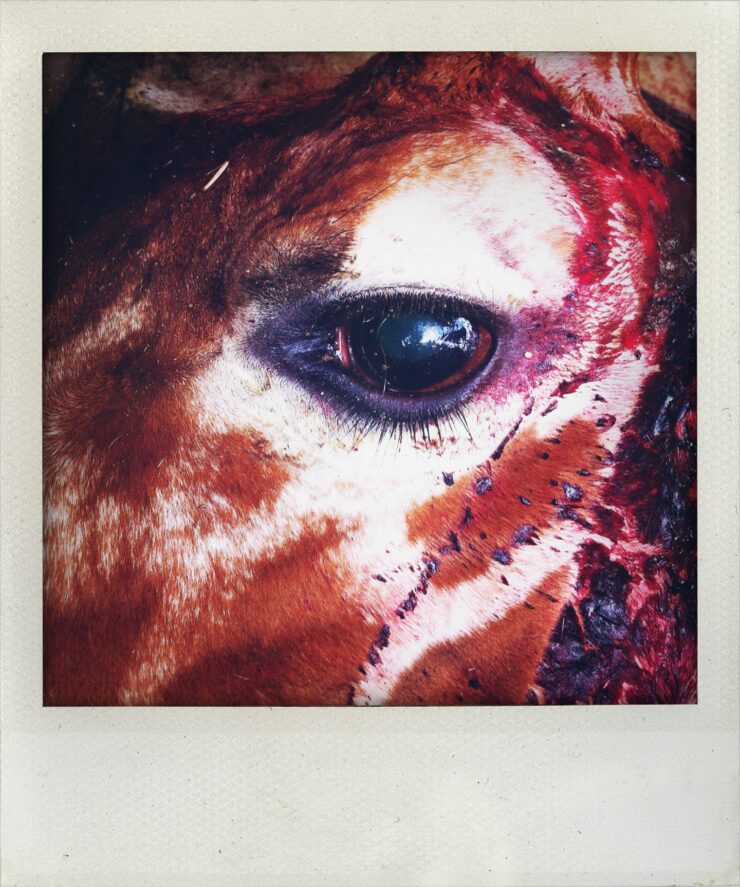

Marius | Didde Elnif | CC BY-NC 2.0

In 2014, global outrage took media by storm after employees from Copenhagen Zoo intentionally killed a juvenile giraffe named Marius by shooting him through the head. An autopsy of Marius’s carcass was performed en plein publique, and visitors—the audience consisted of children and adults alike—were free to ask questions, which in turn were answered by the two performing autopsists. Bengt Holst, the zoo’s director, later appeared in a TV-interview with British Channel 4 News, where he was rigorously questioned by a seemingly disturbed Matt Frei, who undoubtedly chose sides with the many individuals who condemned this ‘unnecessary act of brutal violence’.

In the interview, Holst comes across as reserved, rational, and utterly realistic about the act of killing Marius, which, he says, was done out of pure necessity. Apparently, the zoo lacked space to accommodate a healthy and happy life for Marius, and since gene pools of endangered species such as giraffes are strictly regulated to prevent breeding animals with genetic defects (“Killing Animals”), Holst saw no other option but to put superfluous Marius down. After the autopsy, Marius’s body parts that were not kept for research were fed to the zoo’s lions, which aggravated the disbelief the scene had generated online.

Frei furthermore questioned the validity of the killing’s purported educational and scientific merit, and asks Holst to comment on the perceived difference between pest control in the wild and population control within the zoo’s confines (“Giraffe” 04:47-57). Importantly, Holst grounds his justification in the argument that Marius could not be of any use to the zoo’s conservational and reproductive programme. In consequence, Marius was killed and fed to the lions on the basis of being perceived as a specimen with a function that it failed to fulfil—i.e. have good enough genes to reproduce, which conflicts with Copenhagen Zoo’s presentation of him as a loveable individual, an autonomous giraffe subject.

Central to the discrepancy are ethical concerns that attest not only to the contested practice of zoo animal keeping in general and the way this translates to the creation of taxonomic hierarchies, but also to the cultural structures of signification that underly relationships between humans and other animals, both inside and outside of the zoo. Holst’s position reverberates with the current paper’s scope, but his sobriety about the killing will be thoroughly scrutinised. Indeed, who decides which animals, zoo-kept or not, can or cannot be killed? Even though Holst confidently motivates the zoo’s decision to kill Marius, this case exemplifies the complexity of the tension between animals perceived as individual subjects and those perceived as replaceable scientific objects, or disposable commodities (e.g. meat products).

Using Marius’s death as a case study, I will argue that the public outrage it caused is a case in point for the complex cultural tropes that determine which animals are eligible as candidates for becoming meat and when we perceive animals as individuals or not. Additionally, I will argue that zoos at least in part contribute to the legitimation of killing certain animals for meat, namely those animals that are kept for husbandry. In doing so, I will first give a brief description of how specific biopolitical mechanisms in zoos sustain a taxonomic hierarchy that specifies which animals can die and which cannot. Furthermore, I will show how the foregoing is motivated by a distinction between certain (companion) species as individuals, persons, or friends, and other animals such as farm animals as deanimalised commodities for profit-making.

Biopolitics and Pastoral Power

In “Managing Love and Death at the Zoo,” Matthew Chrulew argues that the study of biopolitics, from Foucault to Agamben, has unduly emphasised human subjects over nonhuman animal subjects (139). By contrast, Chrulew shows that the ultimate biopolitical paradox—that a technique which caters to the fostering of life at the same time dialectically produces so much death and violence—is most conspicuously found within the zoo environment (141). According to him, primarily problematic is humans’ “total management” (144) of animal life within the zoo, accounting for “animal needs” ranging from “dietary, territorial, social [and] behavioural” to “sexual” (144). At the same time, the “unloved surplus” of “breeding programmes are quietly euthanised for reasons of (un)utility,” (139) of which Marius is a telling, yet all but quiet example. This “total management” stands in stark contrast with a development in zoo keeping Chrulew traces from the second half of the twentieth century onwards, where the focus of zoo exhibition seems to have shifted from spectacle to animal welfare, concealing the former in the process.

Dinesh Wadiwel also focuses on the role of animals in Foucauldian biopolitics. In The War Against Animals, he argues that Foucault’s genealogical critique of the transition from sovereign power to biopolitical governance is characterised by a general disregard for the fundamental role of human-animal relationships in the development of biopower. The missing transitional link, that of pastoral power, says Wadiwel, accounts for the shift “from inanimate property (territory) to animate property (the animal, the slave, the body)” and, quoting Foucault, a “power to ‘do good,’ to ‘be beneficent’” (108). He historicises pastoral power and shows how it became an emblematic and transformative political practice that subjectivises individuals that then came to be treated as coherent, controllable and submissive collectives.

Wadiwel further contends that through domination over non-human animal bodies, pastoral power reintroduced the violent aspects of sovereign power into governmentality (109-110). Consequently, he concludes that “[g]overnmentality does not describe the extension of concern for population across sovereignty, but instead describes the entry of pastoral power to the field of human sovereignty over other humans, encapsulated in the governmentality of the State” (116).

Extrapolating from the foregoing, studying zoos in the context of biopolitics is important, because biopolitics explains the process of differentiation between kinds of property, inanimate and animate, and the oscillation of humans and animals between those two categories. However, the assumption that animals are unconditionally seen as animate entities, then, is problematised by the perception of some species as commodities, while others are elevated to a special status; as being in need of protection and conservation, such as megafauna in zoos.

Using biopolitics as a framework for understanding the cultural role of animals not only serves to more effectively probe human-animal relationships. It also gives impetus to approach hegemonic hierarchies between humans mutually, from the perspective of the objectification and deanimalisation of animals. A dichotomous subject-object understanding of specific human-animal interactions thus undergirds the attribution of varying social, cultural and economic roles to different animal species, and, in extension, to different communities of human beings. In Wadiwel’s words: “All the techniques that science can deploy to make live are enabled to foster the lives of (at least some) animals under human care, even if these same animals are only destined for an early death in line with human utilisation preferences” (119).

Pastoral power as described by Wadiwel, and the biopolitical paradox described by Chrulew, seem to have contributed to the establishment of a cultural complex that is founded on an ‘us against them’ logic with accompanying binary categories. For this paper, the most important overarching binary is that of animal versus object. Often times human beings are distinguished from animals in their self-attribution of capacities that are said to be uniquely human. Additionally, according to the logic described in the previous paragraph, the reintroduction of pastoral power into governmentality extends the dialectical logic of capacities/lack to other human subjects, which has been and still is used as a justification for inferiority along ethnic, gendered, classist and sexual lines.

Objectification results in both human-human constellations and human-animal interactions, but is arguably primarily grounded in the latter. Pastoral power thus enables the creation of subjective hierarchies, in the first place between humans and animals, and then within the nonhuman animal domain. In the latter case, nonhuman worth is based on proximity to human capacities and utility for human life, be it consumptive or otherwise. Some of these divisions stem, at least in part, from theological natural orders that are integral to the hegemonic Abrahamic religions, but which, as I will show later on, are also found in other religions, and non-religious human cultures more generally.

In sum, the biopolitical substrate of pastoral power is not merely a political mechanism, it is also a cultural denominator of kinds that categorises animals and places them in social configurations on the basis of their taxonomy, purported use for human sustenance, social role and scarcity: pets, (meat)food, threatened species, working animals, and so on. Ultimately, the place of animals within these social constellations determines whether they can be turned into meat. As I will argue in the following section, zoos are the nexus in which the social, political and economic positions of various animals collide with frameworks of “human ecology” (Smith 61).

Bio-/thanatopolitics at the Zoo

Not all animals are of equal worth to zoos. This inequality shows clearly from Marius’s death, which painfully exposes the hierarchy of value that anchors a rhetoric of dispensability. In “Preventing and Giving Death at the Zoo,” Chrulew argues that “[z]oos produce death not only accidentally … but also deliberately,” among other things through “feeding their carnivores” (224). Chrulew’s pressing arguments thus not only consist of the observation that animal life in zoos is governed and controlled via mechanisms comparable to human biopolitics, they also point at the asymmetry of killing animals outside the zoo (or even inside in Marius’s case) in order to keep those inside alive.

In the same paper, Chrulew primarily discusses Heini Hediger’s concept of “death due to behaviour,” (228) which is a concern for behavioural causes of death among zoo animals as a technoscientific object of study. These causes of death, Chrulew contends, are largely due to “anthropogenic or iatrogenic” (228) influences and “[f]ailure to attend to species-specific requirements in building exhibits” (230). Points of interest range from proper feeding techniques to types of feed, and from “too much bathing” to “failure to prevent … predators from entering the grounds” (230).

In short, our inability to provide zoo animals with proper living conditions in zoos forces us to circumnavigate those bare necessities by catering to “species-specific requirements” rather than individual well-being of the animals in question. Additionally, these species-specific requirements are scientific facts that form the leading basis for understanding how animals should and do behave, to indicate when behaviour deviates from natural behaviour, and to contemplate how deviant behaviour can be prevented. As a result, the scientisation of animal behaviour runs parallel to their objectification, and will occasionally lead to a total abstraction of species from their materiality.

Although this development might not be as prevalent in zoos, it is in the husbandry industry. Ambiguous categorisations and “legal fictions” are employed in the meat industry to sustain fantasies about chickens as commodities, rather than animal subjects with intrinsic worth (Crenshaw 1, 5). For example, Estée Crenshaw argues in “The Domestic Chicken as Legal Fiction” that legal fictions in the U.S. are meant to deanimalise chickens, so that their meat can be cruelly, though legally, harvested. To rationalise the treatment of chickens, they are described as “non-living” and not even considered as animals in the U.S. Animal Welfare Act (Crenshaw 6). Additionally, their lives are constructed as machinic, enabled through their commodification and formalised in their subdivision into roles such as “broilers” and “layers” (10), which echoes Marius’s unutility as a “breeding” male. Last, chickens are referred to as collectives, rather than individuals, because consumers want to eat something, rather than someone (13, emphasis mine).

Chrulew also argues that Hediger’s ethological concerns serve to improve the animals’ living conditions and ensure their “unique subjective Umwelten” (233). At the same time, however, it sustains a fundamentally untenable taxonomic hierarchy. The eradication of death pertains only to those animals that humans deem worthy of living, or rather: that are worth keeping alive, mostly endangered megafauna. The killing of food animals—i.e. cows, chickens, pigs and horses—is but a negligible function that caters towards sustaining this artificial hierarchy. As Crenshaw shows, the legal perception of chickens as non-animals in the U.S. is necessary for them to be seen as meat product, but it does not explain why chickens, but not giraffes, can be deanimalised.

Furthermore, Chrulew coins the term “ethopolitics” to describe Hediger’s methods (233), new Foucauldian “domains of intervention, knowledge and power … [that penetrate] both body and mind, comprehending and managing animals not only as biological organisms but as subjects of phenomenal worlds” (233). In this way, Hediger aimed to create a normative ethics according to which zoo animals are to be studied as individual subjects whose death needs to be prevented using ethological knowledge. At the same time, this creates boundaries between those animals that are definitely subjects, and those that are only dubiously so, or maybe not at all.

The type of death that ethopolitics aims to erase from the zoo environment is thus displaced onto other areas of animal life, for example the factory farm, where ethopolitics itself plays no role and has no power. Even if ethopolitics is present at the factory farm, it is employed as risk aversion that aims to establish thresholds for antibiotic treatment and maximum crowdedness in, rather than catering to the bare behavioural necessities for animals to live normally. Although Hediger sought to understand animals as “subjects of phenomenal worlds,” only specific types of animals are said to be subjective, and thus only few are recognised as being able to experience a phenomenal world subjectively. Underlying ethopolitics is thus a contradictio in terminis that distinguishes animals that can be studied as individual subjects (those that live in zoos or have a protected status outside of it) and those that are still treated as static and disposable objects, mostly food animals.

All of the foregoing points to the assumption that, at least in the eye of a majority of the zoo-visiting public, zoos are and should be primarily concerned with keeping animals healthy and alive, and thus to conserve certain species, regardless of whether they are threatened in the wild. However, as reactions to Marius’s case show, the culling of excess animals, especially those that have a special status, runs counter to the tendency of seeing zoos as life-promoting and preserving institutions.

That many zoogoers are oblivious to the fact that culling is legal in zoos—not only in Denmark, but across the globe (Parker 15)—goes to show that many misconceptions exist about what zoo practice encompasses beyond what is directly perceptible to visitors. Ironically, Marius’s autopsy was announced and deliberately performed publicly and during opening ours, so seemingly obtuse managerial decisions are not necessarily withheld from the public. To the contrary, Marius’s case was presented as a unique and exclusive learning experience. Among other things, a scrutinization of the biopolitical mechanisms underlying these contradictions helps demystify and better understand what is at stake for certain species in discussions about their “right to live,” to phrase it in popular animal rights-oriented words.

The next two sections will discuss in more detail the ways in which species hierarchies have been and still are societally constructed, both in secular and religious ways. First, I aim to synthesise various views about the material distinction between animals and objects that undergirds questions of animal subjectivity and the individual personality of nonhumans. Second, a framework will be proposed for contextualising the outrage about Marius’s death in relation to the tension between animals as individuals and animals as meat.

The Place of Animals in Human Ecology

In “The Problem with Zoos,” Randy Malamud asserts that “it is impossible to argue that zoogoers are learning important ecological lessons” (401). One example of this is that we tend to be more concerned with a single giraffe than with the copious amounts of meat that human beings consume. Malamud further observes that zoo-goers visit zoos to affirm their beliefs about the thriving of certain species and are repelled by confrontational narratives such as global warming, climate change and industrial farming (406), an observation that seamlessly segues into zoos’ rationalisation of serving meat foods. The rhetoric of serving meat, both to visitors and zoo animals, goes hand in hand with a persistent distinction between animals as animals and animals as commodities.

Needless to say, carnivores need meat to survive, but it is not the carnivores’ choice what meats they are fed and where the produce comes from. Additionally, carnivores do not distinguish between their prey and meat, as the cultural significance of “meat” as a concept is only discernible and meaningful to human beings. Thus, something more profound is happening than mere repulsion when zoogoers report to be disgusted by lions that are fed animal carcasses that too much resemble their former states as living animals.

One way to explain these complexities is by looking at how various species figure in human ecologies. In “Attitude of Zoo Visitors to the Idea of Feeding Live Prey to Zoo Animals,” Ings et al. empirically surveyed zoo visitors’ attitude towards the feeding of live prey to carnivores. The primary reason for carrying out the study was to determine to what extent zoo visitors find feeding live prey to carnivores morally objectionable. Ings et al. found that the degree to which visitors were repelled by this idea corresponds to a “hierarchy of concern … which increased from insects to rabbits” (345). Their study focused on three classes of live prey: insects fed to lizards, fish fed to penguins and rabbits fed to cheetahs (345). They furthermore observed that this subdivision “may reflect the perceived taxonomic hierarchy by members of the public in previous studies” (345). It is important to note that the research was conducted among numerous zoos in the UK, and “the data presented … may [thus] not be generalizable to other countries” (346). Discomfort of witnessing the killing thus likely depends on the species’ symbolic meaning and sociocultural status.

Ings et al.’s study suggests that some animals are prima facie seen more as objects, whereas others are perceived as genuine animal companions. Rabbits, for example, are sometimes kept as pets, so that zoogoers are logically more repelled by seeing a cheetah devour a live rabbit than by a lizard gulping a cricket. In “A Form of War: Animals, Humans and the Shifting Boundaries of Community” Justin E.H. Smith argues that the social kind an animal belongs to determines how it can be treated (62). Additionally, he asserts that studying the appearance of these social kinds in human ecology contributes to overcoming the physiological generalisations that guide some of our moral commitments towards various species (63).

For example, Smith states that “the cow functions as a fixed reference point that gives context and meaning to human action” (66). In secularised Western contexts, cows might be seen as commodities that can be turned into beef, whereas in some religious Hindu communities in India, they have an exalted and thus inviolable status. These cultural disparities might be due to a development in Western culture, says Smith, where “animals that [had] a direct impact on human lives, as nutriment, ceased to be perceived at all” (73). In order for this to happen, Smith argues that animals “had to stop being perceived as animals of any sort, but instead as commodities,” (73) and this cultural development created leeway for industrial farming to arise during the later stages of Western industrialization.

In effect, Smith posits that the total deanimalisation of animals created a rupture between those animals that began to be displaced from our ecologies—commodified animals—and companion species and pets that figure in more complex cultural-historical entanglements with human life, such as horses, dogs and cats, which is partly due to the ways in which we anthropomorphise certain animals. Smith concludes by stating that “individual creatures are reduced ontologically to interchangeable instances of a kind, and this kind in turn is conceptualized as having a unique property or end,” (79) which is signalled “by shifting to a mass noun in speaking of an ensemble of otherwise individual animals” (80). Examples are the collectivisation of chickens described by Crenshaw, and the general conception of collections of farm animals as “cattle”. On the other hand, we give pets and companion species names, and treat them according to their unique positions in social configurations such as the family, and their role as national symbols.

To complicate things even further, Banu Subramaniam argues in “The Ethical Impurative” that a rhetoric of purity politics directed at the consumption of meat underlies many of the contentions between the majoritarian Hindu population and Muslim and Dalit minorities in India (259). Hindus see cows as pure and near-sacred, so that according to their religious principles, it is prohibited to consume their meat. Muslims, on the other hand, do not consume pigs, because they see them as impure, and thus rely on the production and consumption of beef. Additionally, most Hindus are vegetarian, so that the killing of cattle in general is a frowned-upon practice. Following fascist developments in Hindu politics, Subramaniam argues that the state mandated regional bans on cow butchering and leatherworking, which negatively affected as many as 2.5 million Muslim and Dalit people (259). She goes on to say that “[b]eef has thus emerged as a potent site for ‘meat politics’” (259), and shows how conflicting religious conceptions of certain species claim not only animal lives, but also human lives. Lamenting these developments, Subramaniam opts for a turning away from unfounded claims to purity, so that future risks revolving around conflicting interests regarding the production and consumption of meat can be averted.

Smith’s and Subramaniam’s arguments are echoed by Cora Diamond, who in her relatively well-known essay “Eating Meat and Eating People” rebuts a line of animal-rights reasoning as put forward by moral rights and animal ethics philosophers such as Peter Singer. She refuses to extend the concepts of human rights and justice to animals, which, in her view, are inadequate modes of argumentation, because this takes human concepts of “justice” and “rights” as a normative basis for animal treatment (467). In turn, this would lead to lines of reasoning that parallel vegetarianism with anti-cannibalism, which in Diamond’s view is unproductive. Instead, she argues that we must look at the ways in which we differ from animals, and the way in which these differences are perceived. In her words, we need to “distinguish the ‘difference between animals and people’ and the ‘differences between animals and people’” (470, emphasis mine).

Discussing a vegetarian propagandistic poem by Jane Legge, Diamond shows the confusion and hypocrisy inherent in the way adults communicate the acceptable norms of human behaviour towards animals to their children. If part of our pedagogy revolves around prohibiting children to “pull the pussy’s tail” (473), then there must also be a way to explain to children the moral reprehensibility of factory farming. In order to achieve this, Diamond proposes to approach animals not from a biological perspective, which would also erroneously ground the discussion in biological and moral capacities and capabilities, but from an understanding of animals as “fellow creatures” (474). Understanding not merely our cats and dogs, but all animals as possible “company” (474) allows for a new kind of “respect for the animal’s independent life” (475), which necessitates an appreciation of animals qua animals, and not as faceless commodities.

Marius is the prime example of zoogoers’ contradictory care for animals with personalities, and their concurrent lack of self-criticism regarding dietary standards. This perceived difference is sustained precisely by the biological arguments of capacities that Smith and Diamond argue against, and upholds asymmetries in the attribution of quality of life to various species. In the last section, I will turn to how tensions between individuality and deanimalisation/animal commodification lie at the basis of the moral outrage about Marius’s death.

Animal ≠ Meat

In “Let Them Eat Carcass,” Jason G. Goldman discusses the idea of “psychological distance,” a marketing trick that obscures animal products to the extent of being unrecognisable to consumers. This associative abstraction allows us to separate “animal” and “meat”. He argues that “psychological distance” be maintained if zoo-goers want to feel comfortable during their zoo visit: “Our moral dilemma is obviously not about meat eating per se, but about the predatory nature of carnivory.” Seeing carnivores feed on animal carcasses that too much resemble a recognisable, live animal confronts us with the idea that humans kill for meat too, usually in a more bestial manner than the “beasts” themselves.

A case in point that exemplifies the previously mentioned study by Ings et al. is described by Brad Haynes in a Seattle Times article about the horse meat industry. There, Haynes observes that in the years preceding 2007, US zoos “have dropped horse meat in favor of beef,” even though “zoos continue to be the largest consumers of horse meat in the United States” (Haynes). The US have made numerous attempts at federally banning the “sale or transport of horses to be slaughtered for human consumption,” and some zoos chose to switch to feeding beef because “zoo visitors might be more comfortable knowing horse was off the menu” (Haynes).

Horses are seen as companion species in the US, which is why some people are naturally inclined to disapprove of using horse meat as fodder for carnivores. Haynes quotes Humane Society’s CEO Wayne Pacelle, who condemns zoos that feed horse meat because they are “contributing to the inhumane treatment of this American icon” (Haynes, emphasis mine). What Pacelle fails to mention, however, is that cows that end up as carnivores’ feed are presumably treated more cruelly and inhumanely than the horses targeted in his condemnation.

Ian Parker makes a similar cultural observation comparable to Goldman’s in “Killing Animals at the Zoo,” a reflective article about Marius’s death in The New Yorker. Parker argues about the Danes that they have “a tradition of pragmatism … about animal death”. Danes, too, are fond of meat and they employ industrial killing methods similar to those in the US. Apparently, they are more open and less squeamish about killing animals per se, hence Holst’s sobriety about Marius’s killing.

Parker further asserts that “[o]ne could argue that certain beloved species should be protected from culling because they’re beloved,” which would explain why Western countries do not serve cat or dog meat as these species are commonly seen as pets. Additionally, Parker’s clever synthesis of different zoos’ reactions to the Marius controversy exposes how Holst “had placed questions about the purpose of zoos ‘in the middle of society’.” In the first instance, Marius’s death was problematic not because a defenceless, innocent giraffe was killed, but because this event disturbed the commonplace illusion that zoos only care for their animals and would never engage in atrocious acts such as liquidating animals with a public image.

Abigail Levin indirectly responds to Parker’s observations in “Zoo Animals as Specimens, Zoo Animals as Friends.” There, she argues that the Copenhagen Zoo’s controversy revolves around the difference between animal individuals and specimens (3). Usually, when we think of laboratory environments where animal experiments are conducted, we presume that these animals are anonymous, have no names or personalities, and are thus replaceable specimens. However, Marius was seen as an animal with a “special status,” a “unique individual, quasi-person … or friend” (3), characteristics that were attributed to Marius by the zoo itself. Thus, Marius’s “singularity” as an “irreplaceable” friend (7), and the fact that Copenhagen Zoo transgressed their perceived obligation of keeping Marius alive, contribute to the moral wrong that was committed.

However, two things should be noted about Levin’s text. On the one hand, she claims that the public outrage followed primarily from Copenhagen Zoo’s failure to fulfil their duties towards visitors, stating that the zoogoers “suffered significant loss” (19). This centralisation of visitors’ loss is an anthropocentric way of framing the discussion that risks devaluing Marius’s intrinsic worth as an individual, who indubitably suffered a more significant loss than the visitors.

Second, Levin does not disentangle the differing social and cultural roles of pets, companion species, zoo animals and food animals, which leaves questions about Marius as a meat product unanswered. She does, however, like Parker, observe that Copenhagen Zoo killed three lions not long after Marius’s autopsy, an event that was significantly less reported than Marius’s case. These lions were presumably not presented as friends as publicly as was Marius, and were therefore less interesting to engage with, both on location and via social media (16-7). Selectivity and accident thus also seem to contribute to the way in which specific animals are perceived, but good treatment will ultimately always rely on the personalisation of specific individual animals.

Conclusion

Concluding her argument, Levin contemplates:

Since zoos are deeply in need of compelling objectives for their continued existence, given the round critiques of their stated traditional objectives, perhaps they ought to take on the cultivation of interspecies relationships as more than a display practice: perhaps a new objective of zoos could be to facilitate friendship relations between the species, teaching and instantiating the morality and compassion such relationships require. (21, emphasis in original)

Indirectly responding to Diamond, Levin proposes that friendship and companionship are to be seen as potent transformative planes of interaction in which to ground our attitudes towards animals in general, not just towards those that have a special status in zoos or as pets and companions. Zoos can contribute to reconfiguring the logic of our animal interactions by foregrounding the fellow creatureness of nonhuman animals. In some ways, they have a moral obligation to do so. That is, if they consider themselves to be advocates for the protection of animal life in general. If zoos somehow succeed at renegotiating our attitudes towards animal lives as integral, rather than diametrically opposite to, our own, new possibilities might arise to adequately address problems of animal maltreatment outside of the zoo, most notably animal cruelty in factory farms and excessive consumption of meat. A renewed sense of “empathy” and a “reconstitution” of animals in cultural narratives are possible approaches to this goal (Wright 28), which aim to bring back into visibility those animals that have been erased from our ecologies. These objectives can be advocated by zoos if they revise their educational and scientific trajectories, not only by listening to their visiting public, but most importantly by listening to how the animal talks back in culturally mediated ways that are otherwise neglected.

Works Cited

Brando, Sabrina, Jes Lynning Harfeld. “Eating Animals at the Zoo.” Journal for Critical Animal Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, 2014, pp. 63-88.

Chrulew, Matthew. “Managing Love and Death at the Zoo: The Biopolitics of Endangered Species Preservation.” Australian Humanities Review, vol. 50, 2011, pp. 137-157.

———. “Preventing and giving death at the zoo: Heidi Hediger’s ‘death to behaviour’.” Animal Death, eds. Jay Johnston and Fiona Probyn-Rapsey. Sydney: Sydney UP, 2013, pp. 223-40.

Crenshaw, Estée. “The Domestic Chicken as Legal Fiction: Cruelty for Profit.” Humanimalia, vol. 9, no. 1, 2017, pp. 1-19.

Diamond, Cora. “Eating Meat and Eating People.” Philosophy, vol. 53, no. 206, 1978, pp. 465-79.

Goldman, Jason G. “Let Them Eat Carcass.” SLATE, 3 January 2014, https://slate.com/technology/2014/01/food-for-pets-and-zoo-animals-they-should-eat-real-meat.html, accessed 25 Mar. 2021.

Haynes, Brad. “Zoos in a pickle over horse meat.” The Seattle Times, 14 August 2007, https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/zoos-in-a-pickle-over-horse-meat/, accessed 23 Mar. 2021.

Holst, Bengt. “Giraffe Copenhagen Zoo Chief: ‘I like animals’.” YouTube, uploaded by Channel 4 News, 10 February 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vuxgAC0dWK4.

Ings, Raymond, Natalie K. Waran, Robert J. Young. “Attitude of Zoo Visitors to the Idea of Feeding Live Prey to Zoo Animals.” Zoo Biology, Vol. 16, pp. 343-47.

Levin, Abigail. “Zoo Animals as Specimens, Zoo Animals as Friends: The Life and Death of Marius the Giraffe.” Environmental Philosophy, vol. 12, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1-23.

Malamud, Randy. “The Problem With Zoos.” The Oxford Handbook of Animal Studies, ed. Linda Kalof. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2014, pp. 434-48.

Parker, Ian. “Killing Animals at the Zoo.” The New Yorker, 8 January 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/01/16/killing-animals-at-the-zoo, accessed 9 Apr. 2021.

Smith, Justin E.H. “A Form of War: Animals, Humans and Shifting Boundaries of Community.” In Animal Minds & Animal Ethics: Connecting Two Separate Fields, eds. Flaus Petrus and Markus Wild. Transcript Verlag, 2014, pp. 59-82.

Subramaniam, Banu. “The Ethical Impurative: Elemental Frontiers of Technologized Meat.” In Meat! A Transnational Analysis, eds. Sushmita Chatterjee and Banu Subramaniam. Duke UP, 2021.

Wadiwel, Dinesh. The War Against Animals. Leiden: Brill, 2015.

Wright, Laura. “Vegans in the Interregnum: The Cultural Moment of an Enmeshed Theory.” Thinking Veganism in Literature, eds. E. Quinn and B. Westwood. Palgrave McMillan, 2018.