Thick descriptions

Entertainment, Education, Extinction: Understanding the Modern Zoo through ZooTycoon 2

By Sanne Teune

After the successful release of the PC videogame ZooTycoon in 2001, Microsoft Game Studios released its sequel, ZooTycoon 2, in 2004. Both games received favorable reviews, and the franchise sold several million copies in total. ZooTycoon 2 reached the top 20 best-selling computer games in the year of its release and maintained that place for at least two more years, according to the NPD’s records (2005; 2006; 2008). The two basic games were supplemented with seven expansion packs, and have been adapted for other devices, such as the Xbox (2013 and 2017) and the Nintendo DS (2005 and 2008). As a business simulation game, ZooTycoon’s premise is to build and maintain a virtual zoo. This requires the player to balance finances, animal maintenance, and various in-game assignments.

While some attention has been given to the original ZooTycoon’s presentation of animals and nature (Opel and Smith; Rothfels), interest in the game series from a cultural or animal studies perspective has been very limited. The sequel has been entirely disregarded, despite the popularity of both games in the years after their release. And, though Opel and Smith argue that ZooTycoon is “a unique site of inquiry into contemporary questions about humans’ relationship to the natural world,” they are less concerned with the zoo as a mediating institution in this relationship, positioning it simply as one kind of enterprise among many others depicted in business simulation games (104).

The current paper instead centralizes the zoo as an essential and, indeed, unique site of animal/human relations. While the game cannot be considered a direct representation of the modern zoo, this paper holds that ZooTycoon and its sequel, often cited as examples of educational video games (see Angelone; Charsky and Mims; Gee et al.), fit within the public’s conception of what a zoo is or can be. Published three years after the original, the creators of ZooTycoon 2 had the opportunity to update gameplay—shown, particularly, in its improved graphics and the addition of a 3D engine—but also to alter its depiction of the zoo as an institution based on feedback on the original game. As such, the sequel is here considered representative of the public image of the zoo in the early 2000’s. This paper analyzes in particular the ways in which ZooTycoon 2 juxtaposes entertainment, education, and conservation as goals of the modern zoo.

The Modern Zoo

John Berger, in his foundational essay “Why Look at Animals,” commented on the presentation of zoos in the eighteenth and nineteenth century as educational institutions. According to Berger, this was a way of obscuring the fundamentally colonial nature of zoos, and their true purpose of displaying a colonizing nation’s wealth and power (Berger 21-22). Helen Wilson considers the educational message proclaimed by modern zoos, which, like Berger, she finds is centered on the “living” encounter between humans and nonhuman animal (Wilson 33). She notes that the purpose of the supposedly educational animal encounter is often to create enthusiasm for animal preservation. She finds this relation between encounter and conservation problematic, as it devalues animals that are not easily encounterable (Wilson 33).

The conflation of zoos and conservation efforts is also discussed by Matthew Chrulew, who frames this relationship in terms of biopolitics. As the zoo increasingly controls all aspects of animal life in virtue of saving it, a tension appears between the preservation of life and the creation of what Agamben has termed ‘bare life’: the life of the individual animal paradoxically becomes obsolete in face of the survival of the species (Chrulew 150). This is epitomized in the system of ‘cryobanking,’ through which animals are maximally abstracted into strings of DNA (148). At the same time, with what Chrulew calls the ‘Hediger revolution’ in the mid-twentieth century, animal welfare became foregrounded as a part of preservation in the zoological garden. As much as possible, the national habitat of an animal was to be recreated, and “the anthropogenic effects of captivity” to be mitigated (144).

Chrulew’s ‘Hediger revolution’ is a play on the Hagenbeck revolution in zoo-landscaping that took place at the turn of the nineteenth century. This new ‘moated’ zoo attempted to improve the zoogoer’s experience by removing visible barriers between visitor and captive animal (Greene 68). In a late-twentieth century rediscovery of Hagenbeck’s vision, Melissa Greene states, zoos have begun to use new technologies to influence both the perception of visitors and the behavior of captive animals, in order to create an even more immersive experience (62). This development lines up with Chrulew’s Hediger revolution. Though Hagenbeck zoos already paid attention to ‘natural’ landscapes, their emphasis was on aesthetics, not the animals’ ecological needs (68). As Chrulew attests, animal welfare has received increasing attention in the past decades, though the balance between non-human animal care and human entertainment in zoos remains tentative. Even as zoos strive to be “a productive power devoted to the nurture of life,” the wellbeing of captive animals easily becomes a means to an end rather than a goal in itself (Chrulew 144).

In their analysis of the original ZooTycoon, Andy Opel and Jason Smith position the game firmly within a capitalist, consumerist framework. Much like wildlife-centric theme parks such as Sea World, they find, ZooTycoon unreflexively commercializes and commodifies nature. In line with Berger’s assessment of eighteenth-century zoos, they argue that any attention paid to research or environmental concerns is merely a “veneer,” hardly obscuring the fact that “profit is the sole measure of success” in the game (Opel and Smith 110). Even more troubling is the game’s suggestion that human control over nature and wildlife is both desirable and beneficial. This is emblemized in the problematic measurement of captive animals’ “happiness,” which Opel and Smith argue is neither knowable, nor achievable “in the confines of captivity” (113). Moreover, the virtual animals’ constant need for new materials to remain ‘happy’—paired with human visitors’ similar demands—places the animal itself in the anthropomorphic position of capitalist consumer, further legitimizing the commodified view of the zoo (113).

Nigel Rothfels also comments on happiness in ZooTycoon, which he posits as a main feature of the game. He reflects that—like any real-life zoo designed since the Hagenbeck revolution—ZooTycoon imposes a distinctively human perspective on animal happiness. It is easily assumed that recreating an animal’s natural habitat directly improves animal happiness, whereas in reality, it is visitors’ happiness that is increased: the visitor imagines that the animal is happy, and therefore becomes happy themself (Rothfels 484). Though less derisive of the game than Opel and Smith, Rothfels also points out other problematic elements, such as its stereotypical attribution of only one type of terrain to each animal species, and its heteronormative suggestion that cohabitation between one male and one female animal is natural and healthy in all cases (484).

Both Rothfels and Opel and Smith focus on gameplay features rather than narrative in their critique of ZooTycoon. As the analysis below illustrates, the two are not always aligned in depicting the goals of the zoo in ZooTycoon 2. Attention is given to both aspects in this paper, with attention to the areas where gameplay undermines the textual narrative.

How to Play

Like its predecessor, ZooTycoon 2 presents the player with an overhead view of rough terrain, and allows them to build exhibits, roads, and buildings to create a functional zoological garden. Animals can be adopted for a fee through the “panda icon” menu, ranging from $1,250 (e.g. the common peafowl) to $50,000 (the giant panda). Using a paintbrush feature, animal enclosures can be freely changed to a landscape from one of ten biome sets. Each animal species requires a specific biome. Plants and rocks can be added to the enclosure, and many types of food, shelters, and toys are available. When the player clicks on an animal, the “zookeeper information” button reveals the biome and items that are suited to that animal. The zoo’s level of fame, measured in five stars, determines the player’s progress. New adoptable animals, resources, buildings, and entertainment items become available as more stars are earned.

The player can click on guests and adopted animals to see their needs and current activities. In the case of guests, the player has the strangely invasive option to access recent thoughts, which may help gauge the zoo’s deficiencies. In a similarly omnipotent style, the player can move animals, people, and natural resources around at will. These features are reflective of the videogame medium much more than of the zoo, but they nevertheless present the natural environment as inherently malleable. In this context, Opel and Smith also point to the prevalence of instant action—constructing, moving, and removing items—in the game as a symptom of consumer culture (114).

Finally, the player can move through the zoo as if walking around through the ‘guest mode’ option. This allows them to care for animals, clean up excrement, empty trash cans, and refill food trays by hitting space bar near the relevant animal or item. These are options for close interaction with the zoo environment that Opel and Smith found lacking in the earlier game (114), which suggests that the producers have made a conscious attempt to narrow the relation between player and animal in the sequel.

Three types of gameplay are available in ZooTycoon 2’s main menu. ‘Campaign mode’ lets the player take over old or unfinished zoos, setting various requirements that must be met within that scenario in order to progress to the next one. In ‘challenge mode,’ a new addition in the sequel, the player creates a new zoo with a chosen amount of start capital, and is periodically asked to fulfill requests in return for money or fame. Finally, ‘freeform mode’ allows the player to build a new zoo with free access to all resources, though some items must first be unlocked by playing one of the other modes. Each of these modes relates slightly differently to the interplay between education, preservation, and endangerment. In considering the implications of gameplay, this paper is concerned primarily with the challenge and campaign modes, as the freeform mode diverges significantly due to the lack of a financial dimension.

Education, Entertainment, Extinction

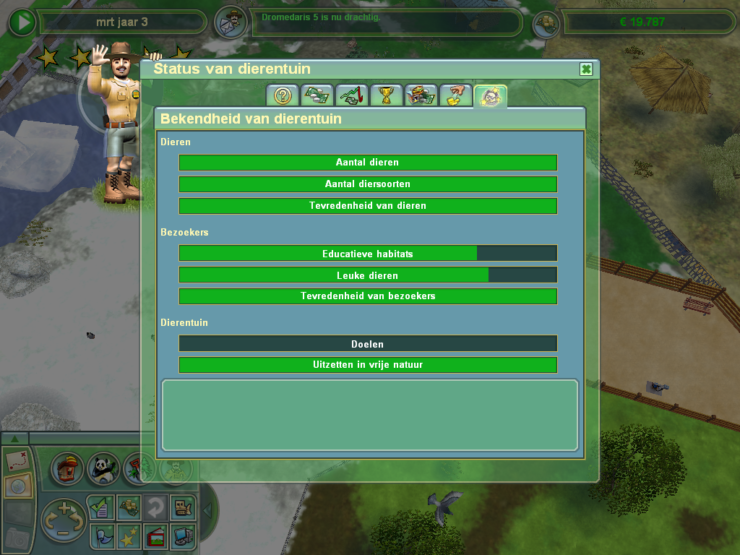

While not central to gameplay, education is highlighted through several elements of the game. First of all, one of the three types of employee that can be hired is the animal educator. The educator requires a podium to talk to visitors; this is the second building under the ‘buildings’ tab, preceded only by the ATM. Donation boxes, one of the primary sources of income, have a separate section for education-related donations, next to animal-specific and general donations. The presence of an educator close to the box will increase donations in this category (“Logbook” 19). Moreover, “Educational exhibits”—achieved by placing animals in their right biomes and making multi-species exhibits—is one of the seven factors in the zoo’s fame rating.

Next to the education of visitors, the zoo is also depicted as a facility concerned with learning about animals. Unlocking new buildings and animal-related items often demands research, which costs time (usually a few minutes in real time) as well as money, going some way to illustrate the effort required for real-life research. The “The Globe” campaign also focuses partly on research. For instance, the first scenario of the campaign is introduced:

The Geography department of a major university has funded a massive biome project to create a facility where the major biomes of the world are represented and can be used for study, research, and education. (ZT2 “The World’s Biomes”).

While research and education are presented here as primary goals to the player, this is immediately nuanced, as it is added that the zoo is expected to “defray” some of the project’s costs “by public admission.”

Money is an essential part of ZooTycoon 2’s Campaign and Challenge Mode, as it was in the original game (Opel and Smith). Like in real life, the adoption of animals, the hiring of staff, and the construction of buildings, pathways, decoration, and enclosures, costs money. The only exceptions are altitude and biome changes, which are free in all game modes. A monthly (in-game) amount is taken from the player’s balance for employee salaries and general upkeep of buildings and exhibits. To be able to progress, the player must ensure that enough funds are coming in, while keeping their animals and guests satisfied. As a result, money—and, at times, profit—is consistently centralized in both narrative and gameplay.

The main sources of income are entry fees from the zoo, profit from food stands and restaurants, and donations. Animal care must therefore constantly be balanced with visitors’ entertainment in order to secure sufficient funds. More visitors will come to an entertaining zoo, and “fun animals” will draw more donations. Similarly, guests are more enthusiastic when they feel that the animals are happy with their exhibits, and will even remark on this on occasion when the player checks their thoughts. The dubious factor of animal happiness that Rothfels and Opel and Smith address thus remains present in the sequel. In Challenge Mode, money can be made by completing challenges, which often involves sending pictures of animals to an interest group.

As Opel and Smith have also addressed (112), an unconventional way to make money in the game is through the recycling of natural resources: the terrain on which a new zoo can be created always contains plants and rocks that can be sold. By using the ‘excavator’ button, the player can instantly remove any number of these resources. Interestingly, there is no reward for putting an animal up for adoption to another zoo. Rather than preventing the commodification of animals, however, this rather gives the appearance of ‘removing’ the animal in a manner reminiscent of Agamben’s bare life. While releasing the animal into the wild—the simplicity of which is troublesome in its own right—raises the fame level of the zoo, and is only possible when the animal’s needs have been fully met, adoption has no such requirements. Its sole function in the game appears to be to lower the number of animals in the player’s zoo when an exhibit has become too crowded.

The theme of animal welfare is taken up repeatedly in the campaign mode narrative. The “Troubled Zoos” campaign, for instance, asks the player to take over zoos that have neglected their animals or otherwise failed to fulfill their needs. While thus acknowledging the fact that zoos can and do fail their asserted goal of protecting animals, the game quickly responds this by suggesting that the failed zoo is either an incidental or accidental occurrence. In one case, the player is presented with a “new facility with the best intentions, but unfortunately, their zoo planners did not understand the needs of their animals” (ZT2 “Raintree Cooperative Animal Park”). It is implied that a proper zoo will fulfill these needs, and conversely, that any zoo that fails to do so is not a proper zoo.

Animal endangerment and the threat of extinction are also recurring themes in the campaigns. However, rather than a moral imperative, conservation is more often linked to scarcity and value. The player should endeavor to collect and breed the rarest animals for their zoos because these will attract the most visitors. As remarked in the “The Globe” campaign: “Unfortunately, animals from Asia are in short supply! Zoos around the world have had difficulty obtaining these treasured animals” (ZT2 “Scarce Asian Animals”). Accordingly, when the player adds endangered species like the Bengal tiger or the mountain gorilla to their zoo, visitor counts and donations drastically increase.

The zoo’s preservation goals are not presented as solely financially motivated. In the “Conservation Programs” campaign, it is asserted that “the birth of any baby animal is a momentous occasion, but the captive breeding of an endangered species an important, proactive way to ensure species survival” (ZT2 “Animal Conservation”). Even here, though, preservation efforts remain connected with the status and financing of the zoo. Immediately following the previous quote, it is added that “guests particularly enjoy seeing baby animals. Endangered species have even more impact on guests, who are more likely to make generous donations when they view such special babies.” While the first quote reveals the game’s uncritical perspective on captive animal breeding, which Chrulew and others have problematized, the addition takes the emphasis off preservation and suggests that the goal was to make money all along.

Animal breeding is integral to gameplay, which similarly has the effect of commodifying preservation practices. Because animals can die of old age, the player needs to ensure procreation in order to maintain the zoo for a longer period of time. Alternatively, animals of the same species would need to be adopted repeatedly; a near impossibility considering the limited available funding in regular gameplay. In order for animals to mate, they must be placed in a fully appropriate habitat and have all their needs met. As Opel and Smith have pointed out for the original ZooTycoon, the game’s approach to animal wellbeing shows little understanding of the effects of captivity (115). Most of the animals’ needs are easily satisfied by placing them in a biome that has been deemed suitable by the game producers. Any additional requirements can be met by hiring an animal caretaker, or by using guest mode to care for the animal with a single tap of a button. This neither represents the real-life difficulty of breeding captive animals, nor the actual needs of these animals. The simplicity of gameplay clearly interferes with the discourse the game is trying to establish.

The centrality of breeding to zoo maintenance is reemphasized in campaign mode, as breeding is a main goal in several of the scenarios. The final campaign, “The Mysterious Panda,” is entirely dedicated to the adoption and breeding of the giant panda. In homage to its endangerment status, the giant panda is the most expensive animal in the game to adopt and the only animal to be unlocked when the zoo’s fame level reaches five stars. The breeding process of the giant panda, however, does not differ from that of any other species in the game, despite the panda being notorious for its trouble procreating in real life (Green). As such, the game not only commercializes animal procreation, but also homogenizes all zoo animals into offspring-producing machines.

Like its predecessor, ZooTycoon 2 is deeply entangled with capitalism. Financial profit is depicted as a major goal of the modern zoo, to be gained through the use of animals as attractions. While the producers have made attempts to centralize the animal, for instance by allowing the player to ‘zoom in’ and directly interact with them, animal welfare remains secondary to economic goals. Simultaneously, there is a tension between narrrative, which seeks to highlight goals such as conservation and education, and gameplay, which posits fame and wealth as the primary symbols of progress. This tension is itself telling: it seems the modern zoo still struggles, like the eighteenth-century zoo Berger describes, to obscure its colonial and capitalist underpinnings.

In presenting a child-friendly, simplified conception of the modern zoo, ZooTycoon 2 thus lays bare some of the contradictions that lie at the heart of this institution more generally. Whether this was (or is) recognized by the average player of the game was, is another matter. Previous study into the gameplay of children has pointed out that different players engage with games like ZooTycoon in substantially different ways, and some will pay far more attention to game objectives or, more importantly, narrative, than others ( McCarthy 54-55). Nevertheless, the game provides valuable insight into the modern zoo as it existed in the public imagination in the early 2000’s.

Works Cited

Angelone, Lauren. “Commercial Video Games in the Science Classroom.” Science Scope, vol. 33, no. 6, 2010, pp. 45. Gale General OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A218882129/ITOF?u=utrecht&sid=ITOF&xid=b4a919bd. Accessed 25 March 2021.

Berger, John. “Why Look at Animals?” About Looking, 1980, Vintage, 1991, pp. 3–28.

Charsky, Dennis and Clif Mims. “Integrating Commercial Off-the-Shelf Video Games into School Curriculums.” TechTrends, vol. 52, no. 5, 2008, pp. 38-44, doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1007/s11528-008-0195-0. Accessed 25 March 2021.

Chrulew, Matthew. “Managing Love and Death at the Zoo: The Biopolitics of Endangered Species Preservation,” Australian Humanities Review, no. 50, 2011, pp. 137–57, http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p111121/pdf/ch084.pdf.

Gee, James P. et al. “Video Games and the Future of Learning.” Phi Delta Kappan, vol. 87, no. 2, 2005, pp. 105-111, doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1177/003172170508700205. Accessed 25 March 2021.

Green, Louise. Fragments from the History of Loss: The Nature Industry and the Postcolony. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2020.

Greene, Melissa. “No Rms, Jungle Vu.” The Atlantic Monthly, 1987, pp. 62–78.

McCarthy, Lauri et al. “In-Game, In-Room, In-World: Reconnecting Video Game Play to the Rest of Kids’ Lifes.” The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning, Cambridge, 2008, pp. 41-66, doi: 10.1162/dmal.9780262693646.041. Accessed 25 March 2021.

NPD. “Essential Facts About the Computer and Video Game Industry: 2005 Sales, Demographic and Usage Data.” Entertainment Software Association, 18 May 2005, pp. 5. Archived on 4 November 2005.

NPD. “Essential Facts About the Computer and Video Game Industry: 2006 Sales, Demographic and Usage Data.” Entertainment Software Association, 10 May 2006, pp. 5. Archived on 21 August 2006.

NPD. “Essential Facts About the Computer and Video Game Industry: 2007 Sales, Demographic and Usage Data.” Entertainment Software Association, June 2007, pp. 6. Archived on 26 March 2008.

Opel, Andy and Jason Smith. “Zoo TycoonTM: Capitalism, Nature, and the Pursuit of Happiness.” Ethics and the Environment, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 103-120, www.jstor.org/stable/40339090. Accessed 25 March 2021.

Rothfels, Nigel. “Zoos, the Academy, and Captivity.” PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America, vol. 124, no. 2, pp. 480-486, doi: 10.1632/pmla.2009.124.2.480.

Wilson, Helen F. “Animal Encounters: A Genre of Contact.” Animal Encounters: Kontakt, Interaktion und Relationalität, edited by Alexandra Böhm and Jessica Ullrich, Metzler, 2019, pp. 25–41.

ZooTycoon 2. Windows PC version, Microsoft Game Studios, 2004.