Thick descriptions

The Potential for True Encounter: The Legacy of Bokito’s Escape

By Merel Hol

On the 18th of May 2007, a male silverback gorilla named Bokito escaped his enclosure in the Rotterdam zoo Diergaarde Blijdorp. The event was the center of much media attention, asking how this could have happened and how it can be prevented from ever happening again. Bokito was such a phenomenon that he continues to be reported on today, as in the NOS article “Ten years later: how is gorilla Bokito doing now?”. Not only does the interest in the gorilla persist, his influence is undeniable in Dutch language. “Bokitoproof”was the Dutch Word of the Year in 2007, meaning “secure against Bokito and thereby preventing escape” or protected against vandalism.

His name has, since then, evolved into an established concept that generally refers to gorilla qualities, including the specific escape characteristic of boldly moving outside of a designated space. The Dutch reveal a deep fascination with the gorilla and his escape, as the influence of the event is evident in both language and culture, and the escape was covered widely. Bokito’s escape fits in the larger narrative of the “monkey on the loose”, which is the subject of tireless fascination all over the world.

His name has, since then, evolved into an established concept that generally refers to gorilla qualities, including the specific escape characteristic of boldly moving outside of a designated space. The Dutch reveal a deep fascination with the gorilla and his escape, as the influence of the event is evident in both language and culture, and the escape was covered widely. Bokito’s escape fits in the larger narrative of the “monkey on the loose”, which is the subject of tireless fascination all over the world.

Bokito was not the only person of interest in the story of his escape, however. Nearly as often reported on was the woman who supposedly agitated the animal, instigated his escape, and who was the only physical victim of his breaking loose: Yvonne de Horde. In the Dutch media at the time, she was positioned as an unstable character who had fallen in love with the gorilla and believed that the gorilla felt the same for her. Many animal behavior experts jumped at the opportunity to correct her famous line that Bokito smiled back at her, informing the public that gorillas consider bare teeth a provocation and that her persistent eye contact with Bokito essentially compelled him to escape and attack her. From the outset, primatologist and professor Jan van Hooff argued against the idea that the woman misunderstood Bokito’s smiling, saying that he had studied videos of Bokito’s behavior around her and it might have superficially seemed threatening that he showed his teeth, but he in fact interpreted it as a “greeting face,” a reassuring gesture to female gorillas. Nonetheless, the interpretation of the incident as being incited by the victim herself stuck around, as well as the ridicule surrounding her feelings towards Bokito. Feeling connected to an animal to such an extent and especially believing those feelings to be reciprocated became a caricature of immaturity and ignorance.

Yet, connecting to animals and experiencing transformative encounters is one of the most heard arguments to continue to keep animals in captivity. It is the core of the “education” aspect, one of the few argumentative pillars that support the existence of zoos. Dr. Dave Hone, arguing for zoos in The Guardian, outlines this: “Many children and adults, especially those in cities will never see a wild animal … Sure television documentaries get ever more detailed and impressive, … but that really does pale next to seeing a living creature in the flesh, hearing it, smelling it, watching what it does and having the time to absorb details.”  A similar argument is made by zoogoers in a Dutch newspaper: “that education is very important because the impact of an animal is bigger if you can see, hear, and smell them. And not everyone has the money to travel to Asia or Africa.” Anecdotal evidence plays an important role in this argumentation, but at least in the Dutch experience, the Bokito-taboo persists: “For Elly Bouwens, Irma, the oldest of a group of elephants in Diergaarde Blijdorp, is more than just an animal. ‘And don’t start to think now that I am some kind of crazy in-love person, but I do feel a special connection’” (ibid.). The transformative connection is an important element of the educational argument to justify the existence of zoos, and yet it constantly needs a disclaimer that it is an informed connection, a relationship based on knowledge rather than merely emotion, as was presumed to be the case for de Horde.

A similar argument is made by zoogoers in a Dutch newspaper: “that education is very important because the impact of an animal is bigger if you can see, hear, and smell them. And not everyone has the money to travel to Asia or Africa.” Anecdotal evidence plays an important role in this argumentation, but at least in the Dutch experience, the Bokito-taboo persists: “For Elly Bouwens, Irma, the oldest of a group of elephants in Diergaarde Blijdorp, is more than just an animal. ‘And don’t start to think now that I am some kind of crazy in-love person, but I do feel a special connection’” (ibid.). The transformative connection is an important element of the educational argument to justify the existence of zoos, and yet it constantly needs a disclaimer that it is an informed connection, a relationship based on knowledge rather than merely emotion, as was presumed to be the case for de Horde.

But meeting and connecting with animals is a common human experience and one that has been thoroughly theoretically investigated. Helen Wilson, for instance, argues that the animal encounter is a transformative relational experience. She positions it as an event that “shocks and ruptures” (25) and that opens up the potential to new ways of thinking and being. Though the concept of encounter is colonial and its shocking effect originates from the hierarchical difference between the two parties, Wilson argues that transformative encounters simultaneously undo this difference by transgressing boundaries and causing confusion. Importantly, this undoing occurs in “experiences of shock, surprise, and rupture” (28) that are spontaneous and unexpected. Something needs to be destabilized in order for the borders to be exposed and broken open. Wilson includes Jane Bennett’s concept of “enchantment” to describe these rupturing moments, in which one has opened up to “the surprise of other selves and bodies”. Wilson mentions several examples of enchanting moments and transformative experiences, such as Kevin Jackson’s encounter with a moose, which surprised and inspired him, and her theory will not be unfamiliar to many who have unexpectedly encountered animals in nature when hiking or camping. Presumably, many zoogoers would nod enthusiastically and emphasize the importance of these encounters for education about ‘wild’ and especially endangered animals. Yet, this argument of enchantment and connection raises the question whether such a spontaneous and therefore transformative encounter is even possible in a zoo environment.

Zoos certainly try. In “No Rms, Jungle Vu”, Melissa Greene outlines how zoo enclosure design first attempted to evoke this feeling of spontaneous encounter in the 1980s: moving away from concrete cages and garden-like paths, the zoo started to strive for wilderness, excitement, and adrenaline. The effectiveness of an exhibit was measured by the “pulse rate of the zoo-goer” (52) and the design of the exhibits started to strive to achieve the illusion that the animals are not in fact in captivity, by camouflaging the barriers and fences and making the zoo-goers uncertain “whether an animal has access to them or not” (65). This type of zoo design, pioneered by Jon Charles Coe in the 80s and now essentially traditionalized, attempts to facilitate exactly the spontaneous, transformative, and enchanted encounter that Wilson describes. Because of the exciting zoo design, zoo-goers might still be surprised by an unexpected encounter with a zoo-animal, despite their natural assumption to see zoo-animals in a zoo. As a genuine encounter would disturb and break open the barriers between species, the zoo instead hides them, creating the illusion that the zoo-goer and zoo-animal are on equal grounds in the encounter. However, the very concept of the zoo renders this impossible. Unlike Wilson’s enchantment, which argues that the world is created in encounter, that beings are “formed in relation” (28), the zoo encounter cannot go beyond or break open the borders that are inherent in the encounter itself. The categorical confusion that is at the core of Wilson’s transformative encounter is impossible in the zoo because of the intrinsic hierarchy in the gaze, governing who is seeing who.

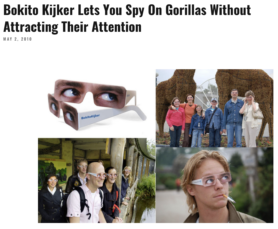

Despite attempting to create a transformative encounter so as to make the zoo-experience more exciting and worthwhile, the zoo cannot change lending the privilege of the gaze solely to the zoo-goer, stripping the zoo-animals of autonomy and agency. A potent example of this in “No Rms, Jungle Vu” are the heated boulders in a Seattle gorilla enclosure which ensure that “the drama of the gorillas’ everyday life is enacted three feet away from the lean-to” (64). The gorillas are technically free to go wherever they like, but their options for privacy are heavily influenced by their need for warmth in cold Seattle winters. The opportunities for the zoo-goers to see and watch the gorillas, then, is prioritized over the gorillas opportunities for freedom and privacy. In “Open Door Policy”, Bradshaw et al. discuss the colonial history of the gaze as well as the zoo, and stress the importance of who gazes and who is gazed upon. Importantly, it emphasizes the “assumed privilege to see an animal when, where, and how one wishes” (138). Though modern zoos might seem a lot less colonial now to the average zoo-goer, having moved on from human exhibits and taking animal needs into account, this privilege persists. Moving beyond Seattle’s heated boulders in the 80s, now many exhibits have cameras and livestreams in places where animals attempt to retreat from onlookers, so that they can still continue to be watched even when they choose not to be. In a similar fashion, when Bokito’s escape was (possibly wrongly) attributed to de Horde’s excessive eye contact, a marketing company created the “Bokito-kijker”,  which hides the wearer’s eyes behind pictured eyes that are looking away, so that even when eye contact is made, Bokito will presumably not notice it. Even in exhibits designed to surprise and excite, human zoo-goers maintain the “right of sight” (Bradshaw et al. 139), which perpetuates the greatest border between them and the animal, and one that cannot be disturbed or crossed by any facilitated spontaneous zoo encounter.

which hides the wearer’s eyes behind pictured eyes that are looking away, so that even when eye contact is made, Bokito will presumably not notice it. Even in exhibits designed to surprise and excite, human zoo-goers maintain the “right of sight” (Bradshaw et al. 139), which perpetuates the greatest border between them and the animal, and one that cannot be disturbed or crossed by any facilitated spontaneous zoo encounter.

The transformative encounter is made virtually impossible by the gaze as well as the zoo-animal’s designated space. Wilson already mentions the problems of “non-human animals that are in some way rendered ‘out of place’”, asserting that especially cities, that are often close to if not surrounding zoos, are “seen as the ‘exclusive domain of humans’ and their domesticated pets” (27). Philo and Wilbert elaborate on these “animal spaces” and connect these to relations of power expressed in practices of designating spaces, categorizing traditions in which “each identified thing has its own ‘proper place’” (6). The zoo offers an ultimate designated space for the animals that it contains: not only are they kept, safely guarded, away from the designated human spaces, but the zoo contains a variety of different spaces for a variety of animals that can also not be mixed. As Greene outlines, the enclosures are designed to fit the different needs of every animal, incorporating “proper plants with the animals, the mixture of appropriate species” (66). Additionally, the spaces cannot be mixed as they are stylized according to the animals that inhabit them, referring back to the countries and continents that they supposedly originate from, despite the fact that many of the animals are born in the zoos themselves. Panda enclosures, for example, heavily make use of Chinese imagery and architecture like the popular “Moon Gate”, a circular window that allows for the female and male pandas to occasionally see each other, based on the stylistic feature that is “typical of traditional Chinese garden architecture and usually employed by the rich upper class”, in order to give the enclosure itself a “Chinese flavor” (Szczygielska 228). The zoo’s designated spaces, then, are safely self-evident and straightforward, further removing the zoo-goers experience with the zoo-animal from any kind of unexpected and therefore transformative encounter.

The widespread excitement and attention for when animals escape, then, as with Bokito in 2007, can be readily explained within the phenomenon of encounter. As illustrated by an article about Bokito’s escape ten years later applying the familiar phrase “De aap is los!”,  escaping zoo animals seem to evoke a particular fascination. This fascination is evident with Bokito’s escape, which enjoyed immensely wide coverage in the news and online, where people shared the video of his breaking loose over and over again. But Bokito is not the only instance of excitement over a gorilla escaping, as similar reporting occurred in 2016 with Kumbuka, a gorilla in the London Zoo. Though his escape was limited to a break into the zookeeper area through two unlocked doors, the media reporting reveals a similar fascination as with Bokito before: The Sun reported that the

escaping zoo animals seem to evoke a particular fascination. This fascination is evident with Bokito’s escape, which enjoyed immensely wide coverage in the news and online, where people shared the video of his breaking loose over and over again. But Bokito is not the only instance of excitement over a gorilla escaping, as similar reporting occurred in 2016 with Kumbuka, a gorilla in the London Zoo. Though his escape was limited to a break into the zookeeper area through two unlocked doors, the media reporting reveals a similar fascination as with Bokito before: The Sun reported that the  “7ft ‘psycho’ beast” was “on the loose” after “[charging] at the glass in its enclosure.” The Guardian offered an account by the zookeepers themselves, who ensured that “Kumbuka did not smash any windows, he was never ‘on the loose’,” correcting the popular discourse of “the ape on the loose”: de aap is los. The sensationalism surrounding gorilla escapes logically follow the cultural fascination for the massive, destructive ape, illustrated by the hugely popular and endlessly remade movies about King Kong. According to Erb, broken loose apes, with King Kong as an especially successful cultural example, are depictions of a “hybridic figure of both terror and possibility” (7). Evidently, gorillas escaping fit a particularly evocative narrative of danger and excitement, much more so than other animals escaping, such as the legless newt mentioned in Philo and Wilbert, who was out of its enclosure for two years before accidentally being found by a gardener (13). The monkey breaking out of his designated space and into the human space means danger for the zoo-goers, an actual adrenaline that the zoo’s hidden barriers could never generate. It is King Kong’s possibility: a chance for a genuine encounter, outside of the zoo’s controlled hierarchies, wherein the animal potentially regains agency.

“7ft ‘psycho’ beast” was “on the loose” after “[charging] at the glass in its enclosure.” The Guardian offered an account by the zookeepers themselves, who ensured that “Kumbuka did not smash any windows, he was never ‘on the loose’,” correcting the popular discourse of “the ape on the loose”: de aap is los. The sensationalism surrounding gorilla escapes logically follow the cultural fascination for the massive, destructive ape, illustrated by the hugely popular and endlessly remade movies about King Kong. According to Erb, broken loose apes, with King Kong as an especially successful cultural example, are depictions of a “hybridic figure of both terror and possibility” (7). Evidently, gorillas escaping fit a particularly evocative narrative of danger and excitement, much more so than other animals escaping, such as the legless newt mentioned in Philo and Wilbert, who was out of its enclosure for two years before accidentally being found by a gardener (13). The monkey breaking out of his designated space and into the human space means danger for the zoo-goers, an actual adrenaline that the zoo’s hidden barriers could never generate. It is King Kong’s possibility: a chance for a genuine encounter, outside of the zoo’s controlled hierarchies, wherein the animal potentially regains agency.

Bokito’s escape, being more extreme than Kumbuka as he actually roamed the park and attacked de Horde, proved to be a transformative encounter for all of the Netherlands. While de Horde claimed she had already encountered Bokito, had felt a connection to him, and had felt transformed by the experience, the rest of the country only truly experienced the encounter as Bokito broke through the borders of his enclosure and forced the zoo-goers to encounter him, seemingly regaining control and power in the skewed relationship of the zoo. As the immense gorilla roamed the park, breaking into a restaurant, he trespassed into the spaces of all the visitors hiding under tables and behind doors, who were involuntarily subjected to his gaze now towering over them. Bokito’s escape exposed the fragility of these spaces and switched the privilege of the gaze, and it was this potential for a very real human-animal encounter that caused the media’s fascination. And yet, Bokito was still in a zoo, in a broadly designated animal space. Even in breaking out of his enclosure, Bokito did not necessarily gain full agency. Despite his intimidating posture and the terrified experiences of the visitors, who felt like Bokito had complete control over the situation, Bokito was not in control; he was in a panic, not knowing where he was and what was happening. To those in the zoo at the time and especially those outside of the situation, reporting on it, it felt as if Bokito gained autonomy and essentially ruled the zoo for the time that he was out. But really, what Bokito chose to do, if he had been truly free to do so, would not have mattered, as he was still controlled by his environment. The zoo had protocols in place and quickly tranquilized him as soon as possible, returning him to his enclosure. Bokito broke the borders of his enclosure space, but could not break out of the zoo space and its control over him. The gorilla’s total agency and control was only perceived, but it was enough to instigate a nationwide fascination. The potential for a genuine encounter, with both sides as true agents, rupturing and breaking open species hierarchy, was momentarily there.

In essence, Bokito’s outbreak was a break in the typical zoo encounter, which despite its best efforts remains facilitated and controlled. A gorilla outbreak is a cause for true adrenaline and threat, surprising and unexpected, and yet, it remains safe in the control of the zoo’s space, which eliminates all spontaneity from its inhabitants as well as its visitors. Nonetheless, Bokito became and still is a phenomenon in the Netherlands, as his name has become a recognizable concept. In addition to it referring to general gorilla characteristics, usually to describe men who are dominant, aggressive, bold, and sometimes even physically resemble a gorilla (“We fall too easily for tall leaders, the ‘bokitos’”),

it also often describes those who break the borders of their designated spaces, be that the conventions of television (“Jeremy Clarkson – the Bokito of the BBC”) or gender roles (“You want a higher salary – how do you take that on as a woman?”). It is undeniable that Bokito’s escape has made an irreversible impact on Dutch culture and language. Arguably, this is because of the excitement of his breaking the borders of his designated space and offering the potential of a true encounter to all witnesses. Bokito’s escape is the most elaborate of gorilla escapes so far, and it shows. As Bokito seemed to become an independent agent for just a moment, the Dutch media and their readers felt the excited fear of encountering a zoo animal on equal terms, to eventually be glad that he was safely returned, perhaps even comfortably reassured in the comfort of human dominance over such an intimidating, strong animal. In attempting to meet the desire for animal-human encounters, those connections that support its apparent educative value, the zoo offers an illusion of enchantment, but might offer it much more in its instances of escape, when the borders seem to be truly broken open. Still, even in these moments, the zoo retains control, and the agency gained by its escapees remains only perceived.

it also often describes those who break the borders of their designated spaces, be that the conventions of television (“Jeremy Clarkson – the Bokito of the BBC”) or gender roles (“You want a higher salary – how do you take that on as a woman?”). It is undeniable that Bokito’s escape has made an irreversible impact on Dutch culture and language. Arguably, this is because of the excitement of his breaking the borders of his designated space and offering the potential of a true encounter to all witnesses. Bokito’s escape is the most elaborate of gorilla escapes so far, and it shows. As Bokito seemed to become an independent agent for just a moment, the Dutch media and their readers felt the excited fear of encountering a zoo animal on equal terms, to eventually be glad that he was safely returned, perhaps even comfortably reassured in the comfort of human dominance over such an intimidating, strong animal. In attempting to meet the desire for animal-human encounters, those connections that support its apparent educative value, the zoo offers an illusion of enchantment, but might offer it much more in its instances of escape, when the borders seem to be truly broken open. Still, even in these moments, the zoo retains control, and the agency gained by its escapees remains only perceived.

Works Cited

Bradshaw, G. A., Barbara Smuts, and Debra L. Durham. “Open Door Policy: Humanity’s Relinquishment of ‘Right to Sight’ and the Emergence of Feral Culture.” Metamorphoses of the Zoo: Animal Encounter after Noah, edited by Ralph R. Acampora, Lexington, 2010, pp. 137-154.

Erb, Cynthia Marie. Tracking King Kong: A Hollywood Icon in World Culture. Wayne State University Press, 2009.

Greene, Melissa. “No Rms, Jungle Vu.” The Atlantic Monthly, Dec. 1987, pp. 62-78.

Philo, Chris, and Chris Wilbert. Animal spaces, beastly places. Routledge, 2000.

Szczygielska, Marianna. “Pandas and the Reproduction of Race and Heterosexuality in the Zoo.” Zoo Studies: A New Humanities, edited by Tracy McDonald and Daniel Vandersommers, McGill-Queen, 2019, pp. 211-236.

Wilson, Helen F. “Animal Encounters: A Genre of Contact.” Animal Encounters: Kontakt, Interaktion und Relationalität, edited by Alexandra Böhm and Jessica Ullrich, J.B. Metzler, 2019, pp. 25-41. ProQuest.