Thick descriptions

Breakfast with the Bears: Three Bear-ish Encounters

By Karlijn Herforth.

Introduction

Although it is not recognized as an official holiday, many Dutch people see the day after Ascension day as part of a long weekend. This and a particularly good weather forecast might explain why the many families, including packed strollers and grandparents tasked with keeping an eye on excited children, that pass me by while I stand waiting at the entrance of Ouwehands Dierenpark in Rhenen. It occurred to me that I did not need to enter the park to research the relationship between humans and zoo-animals for the complexity of the topic was present in the behaviour of people all around me. I overheard parents referring to the “beasts” inside the zoo and telling children that they should not take pictures of the carp in the pound situated before the zoo entrance because they would want to see the “real” animals. I was surprised by toddlers who were being pulled along by a parent through a leash on their backpacks and seemed to have as little freedom over their movements as the caged zoo animals. I also observed how two salespersons of a well-known Dutch lottery and official partner of the zoo, “Bankgirolotterij,” attempted to talk people into buying something. We apparently also appeared as potential customers because the woman approached us when we started moving to the long queue. We never got to hear the whole sale pitch because I told the woman that we were actually in a hurry to enter the park because we did not want to miss the first part of the zoo’s program, namely “The giant pandas having breakfast.”

Ouwehands and giant pandas

When you arrive at Ouwehands, a billboard promises you a unique visitor experience because Ouwehands is the only zoo in The Netherlands in possession of two giant pandas. The pair, Xing Ya and Wu Wen, were presented as a symbolic gift from the Chinese government and arrived in 2017. Ouwehands may keep the pandas for 15 years but is obligated to pay 1 million dollars each year to China for panda conservation programs. It is thus not surprising that the zoo has capitalized the uniqueness of the pandas into one of their biggest selling points to earn this investment back. So far the panda arrival has not lead to more visitors, but the revenue has increased by 50% in the last two years due to more business events in the zoo and the sales of panda souvenirs (Verburg.

Because we did not want to miss the demonstration, we rushed towards “Pandasia” and noticed how the enclosure of the pandas is designed to make you feel as if you were walking in China (fig. 1). The building is a large Chinese pagoda, with all the information signs in both Dutch and Chinese. The description of Pandasia emphasizes that the whole building is ‘traditional,’ from how the roof was built to the authentic colours and symbols. This is not only the most newly renovated part of the zoo (costs: 7 million euros) but also the place with the strongest national identity, for no other enclosure is so intricately tied to a culture and a language. The complex not only houses the pandas, but also includes a Chinese restaurant and an elaborate gift shop where you can buy almost every ordinary object in panda style. The beauty of the enclosure has been acknowledged internationally as Ouwehands Zoo has won twice the price for best and most beautiful giant panda enclosure at the Giant Panda Global Awards (Rooien).

But after we get a glimpse of the sleeping panda in the indoors enclosure, I cannot help but notice the stark contrast with the rest of the building. Whereas the whole complex is draped in Chinese architecture, the design for the panda enclosure lacks any trace of nationality. The walls are painted with scenes from nature, but there has been no attempt to cover up the metal doors, disturbing the illusions the paintings conjure. It was crowded with people around the glass to get a good view of the panda, but the crowds quickly disappeared when an entertainment spokes figure of the zoo announced that the breakfast ritual was about to take place in the outside enclosure. We kept watching the panda for a little while longer, enjoying the sudden quietness around us for a moment, before joining the other exited visitors for the panda’s breakfast.

Fig 1. The entrance of Pandasia. It is unclear what the Chinese inscription on the arch means; presumably “Pandasia.”

Breakfast with Pandas

The scheduling of the pandas having breakfast right after the zoo opens is a strategic move of the zoo to give an incentive for visitors to come early. It also distributes the crowds of people nicely through the park; there are families slowly following the indicated route and people like us who rushed through half the park, including ignoring the savannah and the giraffes, to reach Pandasia. But the idea of a breakfast ritual also serves as a strategy of identification with the animals. The pandas are draped in foreignness, both due to their overemphasized nationality, the outstanding grotesqueness of how they are turned into merchandise, and in relation to the far less exuberant buildings of the zoo. Their unique foreignness is thus juxtaposed with the ordinary event of breakfast, which has for humans a particular social and anthropological importance. It is the first meal after a physiological break with nocturnal unconsciousness, signifying the transferring state of “nocturnal dimension of abandonment, unconsciousness, and revelry [to] the daytime dimension of awareness, identity, and community” (Affinita et al 3). The notion of breakfast indicates a similarity between an important human ritual and the food-centred lifestyle of the panda as bamboo-eating is something typically associated with pandas, but it also implies that the visitor is provided with an authentic and innocent view on a panda that has just woken up to get ready for the day.

As a strategy of creating connection with the animals, the breakfast is part of the larger importance placed on the act of eating in the zoo. Food consumption is everywhere; I continuously watched families snacking while visiting animals and even in the enclosure of the sea lions you could smell the hotdogs and fries from the restaurant. Food draws out the basic similarities between humans and animals, especially if given social or cultural importance such as associated with the ‘breakfast,’ but the act of eating also becomes something in which we join the animal, identify with it. The many people on benches watching the pandas eat while also eating become in a sense, through the point of looking at the animal while eating, a bit like the panda bear. After all, we joked the whole day about when we should plan in our own “voedermomenten.” In addition, the breakfast ritual offers the visitor a well-known image of the panda eating bamboo, which is precisely the picture we could take (fig. 2). It reproduces the cute stereotypical idea people have about pandas that will help to sell the many items of panda merchandise in the Pandasia complex.

Fig 2. Xing Ya enjoying his breakfast.

But as we listen to the caretaker talking about the kinds of foods pandas eat and their behaviour, it becomes clear that the identification process through the act of eating is fabricated. The caretaker explains to the visitors that pandas do not have any notion of specific meal rituals. They eat and sleep and eat and with this pattern, every meal is a breakfast and it thus loses particular significance. The pandas are given food on specific times in the zoo, but they can decide whether they want to hoard all the food until later or eat it directly. Are we then watching a happy panda surprised by the breakfast gathered for him or an animal used to the routine that requires performing the digestion of food in front of hundreds of clicking cameras? Even the caretaker underscores the complex juxtaposition when she remarks that when the pandas are fed in privacy, they eat from her hand. It implies a level of intimacy with the animals that we can never experience, indicating that the visitor only gets a fabricated glimpse into what true interaction or identification with the animal could be like. In addition, the food presented in the zoo to consume by visitors reinforces the superiority of humans to consume animals literally, since the vegetarian options were limited and none of the restaurants had any vegan options. Thus the act of eating centralized in the zoo is an example of what kind of complicated relationships are fabricated with the zoo-animals for the purpose of identification or reducing the foreign otherness of the animals.

Climbing like a Bear

The idea of becoming or identifying with the animal is imagined differently with another bear species. After visiting Pandasia, the general walking route takes us to forest enclosure of the brown and sun bears called “Expeditie Berenbos” which is a shelter for adult bears recuperating from a life in the circus industry. Judging from the cabbages lying around everywhere, the ‘breakfast’ ritual of these bears happened before the park was open to the public. Identification is thus not derived from the act of eating, but this park is all about rekindling with the bears through adventurous climbing (hence the name of the park). When you approach the entrance of the forest, you are presented with two options. You could either walk the wooden trail across the enclosure or climb into a path made out of nets and ropes a few meters above the ground (fig. 3). Fully exploring the chance to do actual field research, I excitedly followed many children and some parents into ropes built for comfortable movement if you are at least one meter shorter than we were. This ‘climbing’ is of course in no way similar to how a bear climbs (we do not vertically ascend a tree) but our stumbling using hands and feet become the closest to what human climbing in a safe environment for children can be. While waiting until the children with sudden fears of heights are being moved forward by parents, we try to get a good look at the bears. The bears sometimes walk underneath the climbing path, but they mostly move away from it (fig. 4). The forest suggests a spacious location for the bears and that are indeed many places to hide from the gaze of the visitor, but this is also the only enclosure in which we are literally above the animals and evade their privacy from all sides.

Fig. 3. Climbing in the ropes.

Fig. 4. The bears.

As with the pandas, the identification with the bear through enacting something stereotypically associated with the bear’s behaviour is not natural but fabricated on many levels. The habitants of the “Berenbos” are a mix of European brown bears and sun bears. Adult brown bears seldom climb trees due to their claw structure and heavy weight, but the sun bear is well known climber, just like the cubs of brown bears. According to the information signs, the enclosure of the bears is built to simulate their natural behaviour. But although we have fun while re-enacting the climbing, the bears are prevented from sharing this activity with us as all the low hanging branches of the trees are cut down to prevent climbing that may lead to escaping the enclosure. The stark separation between humans and animals is also underscored by one particular sound we hear during our climbing adventure, namely the sound of electric sparks following an electric fence being activated (fig. 5). The zoo attempts to conjure the illusion that both species walk the same path and share similar spaces, for example by including the footprints of bears in the concrete trails (fig. 6), but the sound of electric fences disrupt the feeling of being one.

Fig. 5. The fences in the enclosure.

Fig. 6. The bear prints.

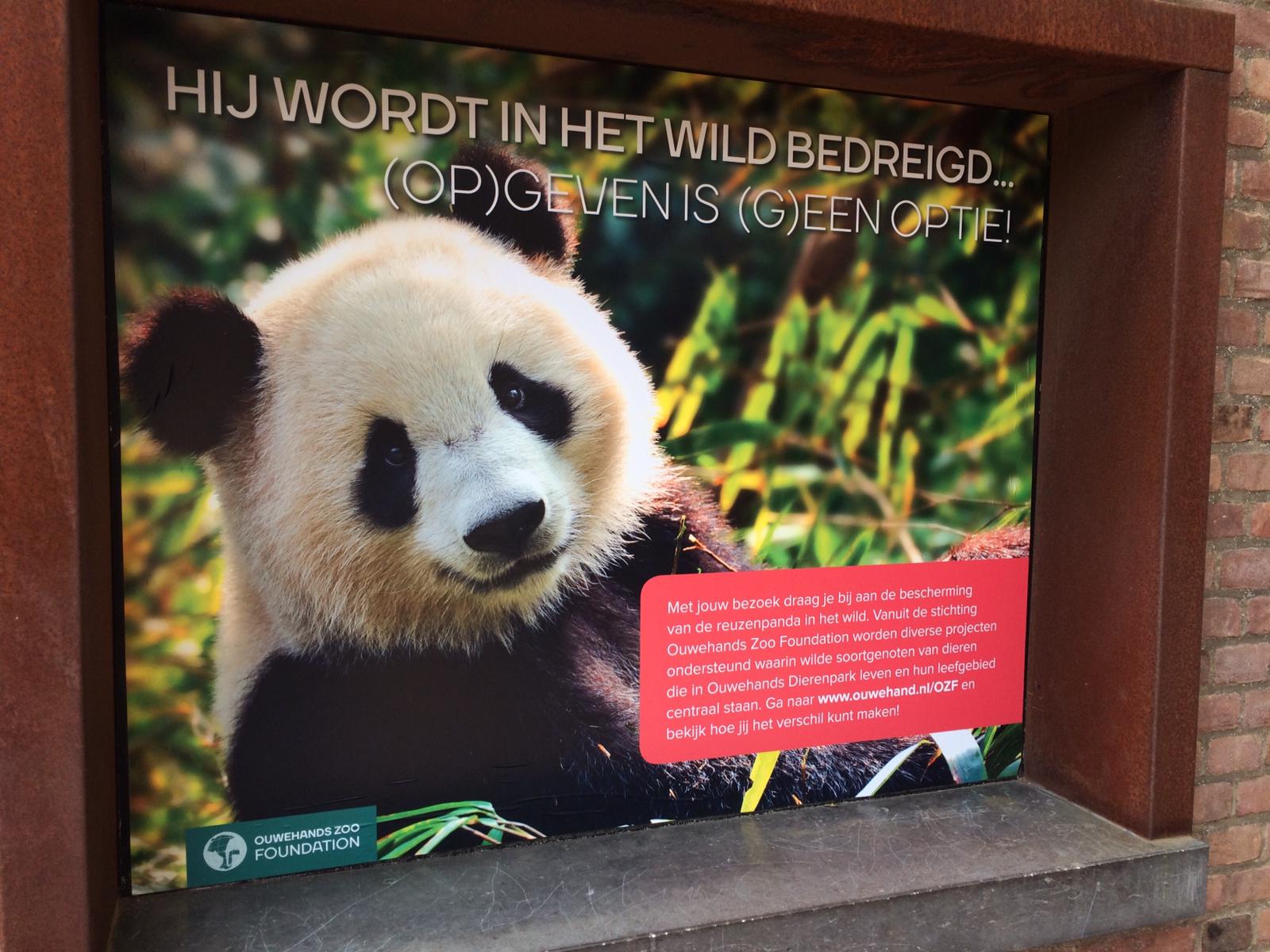

Becoming Bear-ish

What does the sharing of rituals and movements of the animal and human lead to? The zoo’s suggestion that we can eat (breakfast) together with pandas or climb like a bear can be interpreted as a way of ‘becoming’ the wild animal that reduces its otherness. As Brian Massumi articulates, this is “an identificatory confusion [that] is overlaid upon the category separation inherent to the institution of the zoo” (72). The becoming is not so much about the lived actualities of the zoo-animal or about the authentic experiences of a bear. It is a process of being bear-ish; the embodiment of stereotypical character aspects of animals who often cannot exhibit the mentioned behaviours within the confinements of the zoo. For example, the climbing proposes a similar experience to the ‘wildness’ of the animals that is not accessible to the bears in the zoo: “The horror of the visible stifling of the animals’ vitality is converted into fun—in large part the fun of recognizing oneself in the other” (82). The becoming is thus asymmetrical not only because the activity that is supposedly the identification between human and animal is not available or foreign to the animals, but also because of the uncertainty of the zoo animals themselves: “Zoo animals are not domesticated but are also not wild … they are body doubles, stand-ins for the real animals” (Braverman 823). As Massumi indicates, the becoming is a confusing and complex process of entangled ideas we have about animals, the ambiguous meaning of the wildness of zoo-animals themselves and the investment of the zoo in this process for its own purposes. Being bear-ish is thus not about ‘real/wild’ animals but simultaneously the outcome of the identification process is precisely to make people take part in conservation programs that affect real animals outside the zoo. You cannot pet the brown bear, but if you share a similar experience and become to an extent like the bear, you may feel empathy towards their struggles. The zoo is invested in producing experiences that help us identify with the animals at large so that after your climbing adventure, you will put money in one of the many donation boxes. Similarly, the breakfast ritual emphasizes the cuteness of the panda and suggests that you as visitor do not want the giant pandas to disappear; thus you are confronted at the entrance/exit of the zoo with a sign about the need for donations to save the panda (fig. 7). The panda sign reads that “with your zoo visit, you are contributing to the conservation of the giant panda in the wild.” Thus zoo animals stand in for wild animals to call upon the help of humans to save their species (Braverman 811).

Fig. 7. The sign at the entrance/exit of the zoo.

So the visitor, like Braverman points out, is forced “to feel responsible for the disappearance of [the] environment and to react accordingly by donating money” (829). Consumption becomes an ideology of redemption that may save animals (829). But these conservational efforts of the zoo also extend beyond physically visiting the animals. On June 16 of this year, a new television program aired that was filmed in Ouwehands called “Het echte leven in de dierentuin” (real life in the zoo). The program characterizes itself for the unique perspective given on the animals, because everything is filmed 24 hours a day by hidden cameras on places you cannot access as a visitor (NTR). Because the program is partly produced by the zoo’s conservational non-profit Bears in Mind, it is again aimed at appealing to the viewer to care about the act of conservation. Thus what becomes clear from these examples is the paradox of animal identity politics in the zoo; the becoming is not about the animals around the visitor because the similar markers of identity are fabricated or not available to the zoo animals yet its outcome does impact the wild animals outside of the zoo.

How to become polar bear-ish?

Fig. 8. Part of the polar bear enclosure of the polar bear.

A paradoxical becoming is then part of the zoo’s strategy to boost ideologies of conservation and empathy, but the breakfast ritual and climbing are both situations associated with positive affects like fun. What happens if the only affect available to become bear-ish is a negative one? Having regained stability on the wooden path crisscrossing through the bears’ enclosure, we resumed our walk through the zoo. After a first glance on the map, it seemed as if Ouwehands did not have any polar bears. I was a little bit disappointed but also relieved; the weather forecast said that it was going to be above 30 degrees Celcius the following days. But alas, the bright blue plastic walls came into view which signalled the presence of Arctic animals. The enclosure of the polar bears, which was built in 2000, seemed rather old as the plastic walls were grimy and in some ponds the water was so filthy that the zoo could have introduced the “Green Polar Bear” as a new species after the bear had swum in it (fig. 8). The white plastic ice blocks on which children were watching the animals was a stark contrast with the green grassy grounds on which three polar bears where resting. One of the many people watching the bears was an observer of Ouwehands Dierenpark, a woman with a clipboard and a timer writing down the behaviour of the three polar bears. Realising this was probably our only chance to talk to someone of the zoo, we moved to stand next to her. Occasionally a visitor would ask the observer a question like if the polar bears were not extremely hot this far away from the ice. She told the visitor that to some degree, the bears get used to it and they can always go swimming to cool down (the water in this enclosure looked fresh). But her answer was rather hesitant and uncomfortable; she seemed aware that she could not reassure the visitor that the polar bears were in a ‘normal’ environment.

At this point, one of the polar bears got up and started pacing in a circle, again and again. Someone around me remarked that the bear was “aan het ijsberen” and how the bear seemed rather sad, following his circle. We were watching the polar bear longer than the usual visitor of the enclosure and after seeing me writing things down, the zoo observer asked what we were doing. After explaining our project, she told us that she was observing the polar bears each day to study how the enclosure could be improved. The caretakers were thinking about how the bears’ environment could be enriched and given extra stimulus because the zoo wanted to avoid the kind of pacing we were watching. The bear’s circles were unwanted movements, because they evoked feelings of pity and sadness for the captivity of the animal. The observer did not explain why polar bears pace, but studies link abnormal pacing around the edges of enclosures with frustrated escape desire or ranging behaviours. It may also be a coping mechanism to deal with chronic stress caused by noise, to which polar bears are very sensitive (Cless and Lukas 312).

The encounter with the observer pointed out that the zoo is invested in evoking the right kind of empathy that they can profit from. Pity and criticism for caging the polar bear in a warm outdoor enclosure is not going to sell stuffed animals in the gift shop. Becoming polar bear-ish in this situation would be embodying a sense of restlessness, finding a way to cope with too much stimuli of humans. It is a negative affect of the zoo which ironically I could personally relate to the most: after three hours in the zoo, I was completely worn and stressed out by the excess of sounds and humans all around me. Of course, the negative feelings could be subverted to encourage behaviour invested in reducing climate change to prevent polar bears only being able to live in zoos, but this was not the main feeling of the visitors around us. In contrast to the pandas or the brown bears, there was no major positive attraction to become bear-ish or gain identification, which only further emphasizes the zoo’s need for intervening in potential negative animal behaviour and to install processes of becoming that fit their ideologies.

Embracing playful bear-ishness

What becomes clear is that it is difficult to untangle all the figurations built between humans, zoo-animals, wild-animals, and our supposed conceptions of what animals do. It also asks questions about how becoming could be envisioned differently in a zoo; could there be a sense of embracing the animal’s being that does not rely on problematic anthropomorphic assumptions? If I reflect on our visit to the zoo, the feeling that has stayed with me the most weeks after our field trip was the emotion of joy and playfulness I experienced in the climbing ropes that were occupied with children. Massumi indicates that the play of children proposes a different kind of embodying animals. The identification of children with animals through play is not a simple transfer from essential behaviour of the animal to the human, an interaction that could on the surface level describe the climbing paths, but “an intuitively aesthetic vision of [the animal] as a dynamic form of life” (84). The child transposes the style of an animal into their own creative corporeality instead of becoming ‘the’ animal (83). Thus the child “places itself in the field of transindividual tension …. what is at play is the immanent relation of modulation … lived in proximity” (85). This kind of becoming, of being bear-ish, takes into account the different lives of humans and animals but nonetheless embraces the other as a form of life that creatively can be embodied. Proximity seems a productive approach that takes into account the problematic tensions of the climbing path and the non-climbing bears while also critically recognizing how bear-ishness is carried out. Massumi talks about the ability of children to do this kind of playful work, but as an adult I could still feel a similar kind of process working on me. And perhaps some of the parents that accompanied their children into the climbing ropes felt something too; a weird feeling of fun or just a question of why the children could climb in the bear enclosure and what that may lead to. The sense of play confronts every visitor in the zoo in a different becoming of the animal that is less focussed on conservation ideologies or fabricated markers of identity. At the end of the day, we became a bit more bear-ish in many ways, but it is the one becoming engaged in creativity and understanding of proximity that I remain the most hopeful about in gaining an understanding of the animal’s being in the environment of the zoo.

Works Cited

Affinita et al. “Breakfast: A Multidisciplinary Approach.” Italian Journal of Pediatrics, vol. 39, no. 44, 2013, pp. 1 – 10.

Braverman, Irus. “Looking at Zoos.” Cultural Studies, vol. 25, no. 6, 2011, pp. 809 – 42.

Cless, Isabelle and Kirsten Lukas. “Variables Affecting the Manifestation of and Intensity of Pacing Behavior: A Preliminary Case Study in Zoo-Housed Polar Bears.” Zoo Biology, vol. 36, 2017, pp. 307–15.

Massumi, Brian. “The Zoo-ology of Play.” What Animals Teach Us About Politics. Duke UP, 2014, pp. 65 – 91.

“Over het echte leven in de dierentuin.” NTR: Speciaal voor iedereen, ntr.nl/Het-echte-leven-in- de-dierentuin/344, accessed 29 June 2019.

Rooien, Femke van. “Pandaverblijf Ouwehands weer mooiste ter wereld.” AD, 18 Feb. 2019, ad.nl/utrecht/pandaverblijf-ouwehands-weer-mooiste-ter-wereld~a31f4bea/. Accessed 12 June 2019.

Verburg, Martijn. “Omzet Ouwehands stijgt flink door reuzenpanda’s.” AD, 31 May 2019, ad.nl/utrecht/omzet-ouwehands-stijgt-flink-door-reuzenpanda-s~aeba0265/. Accessed 12 June 2019.