Thick descriptions

Zoochosis

By Eamonn Connor.

Zoochosis

We are met by a bright white sign: ‘Malaise bonte marter – Yellow-Throated Marten’. A previous visitor has scratched the surface of the sign, cleaving through the didactic and severing the head of the oblivious specimen drawn perched on a branch in South-East Asia. The description at Artis Zoo reads: ‘Most species in this family live alone, but the yellow-throated marten is often seen in pairs’. For now, I can spot only one in the enclosure, perched still on a branch, mirroring its imaginary counterpart.

The first written description of the yellow-throated marten in the Western World is given by Thomas Pennant in his History of Quadrupeds (1781), in which he named it ‘White-cheeked weasel’. However, the existence of the yellow-throated marten was considered doubtful by many zoologists, until a skin was presented to the Museum of the East India Company in 1824 by Thomas Hardwicke (Horsfield 98). Unlike its cousin, the more famous pine marten, the yellow-throated marten has relatively short fur. I observe it through the mesh that separates human from animal; the top of the head is blackish brown with shiny chestnut highlights. The ears are yellowish grey and that golden tone arches down along the surface of its back. The chin and the lower lips are indeed pure white, breathing clouds into the frigid air of Artis Zoo. The marten meets my gaze. It looks hungry. The sign informs me that these small creatures are ‘capable of hunting down and catching musk deer’. I am suddenly thankful for the mesh barrier.

The ferns within the enclosure have been carefully trimmed to allow for maximum exposure as I scan for the second marten. Following the roving gaze of the first animal, I spot the prize. Matthew Chrulew notes that, ‘zoos require the physical presence of animals within an ordered space suitable for exhibition’ (181), and this element of visibility by enclosure is evident throughout these cages housing quadrupeds; there is no escaping my gaze. The second marten is running laps along the side of the enclosure. I watch it for nearly ten minutes as it runs to one end, leaps up to touch the mesh, then does the same on the other side, and so on. Its partner seems concerned, but at least it didn’t pay 23 euros for the view.

These cognitive and behavioural effects are so regularly witnessed on animals in captivity that it has been given its own name – zoochosis: a condition of obsessive, repetitive behaviours that serve as coping mechanism to the stress zoo animals experience while living in artificial environments with little to no stimulation (Chutchawanjumrat 14). There is a groove in the sand beneath the marten, a material testament to its psychosis. In The Panther, Rainer Maria Rilke writes of his subject, exhibited in the Menagerie of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris:

The easy motion of his supple stride,

which turns about the very smallest circle. (112)

Captive animals have been documented, from New Zealand to Egypt to the U.K., U.S. and the Netherlands, to exhibit symptoms of neurological distress. According to Chutchawanjumrat, zoochosis can include self-mutilation, vomiting, excessive grooming, coprophagia (a symptom observed by this writer in graphic detail when passing the Artis gorilla enclosure), along with anxious tics like the excessive pacing of the yellow-throated marten. While the enclosure certainly looks ‘naturalistic’, Fabregas points out that ‘naturalistic exhibits and expansive enclosures exist only to please the eyes of human visitors’ (371). These ‘enhancements’ do little to address the persistent issue of the abnormal yet repetitive behaviours displayed by the marten. What does seem to be alleviating zoochosis is a process known as ‘enrichment’, part of a five-year strategic zoo planning at Philadelphia Zoo. Enrichment encourages closer human-animal encounters and seeks to provide myriad forms of physical and cognitive stimulation (Chutchawanjumrat 22). The focus on ‘novelty’ recalls Brian Massumi’s foregrounding of play in What Animals Teach Us About Politics; against the traditional mechanistic picture of animal life as blindly, predictable instinctual, Massumi insists on the primacy of spontaneity, vitality and creativity in the immanent development of life (19).

I see no evidence of play in the marten enclosure, and in no sense does the space cultivate interspecies encounters or human-animal contact. Passing visitors giggle at the marten pacing back and forth. A novelty indeed! I remain a spectator. The marten remains a spectacle. For the most part, animals live in the present (Chutchawanjumrat11). I was already looking forward to leaving the zoo, but trapped in a mesh enclosure, the marten’s present was a nightmare from which it was trying to awake – still is, I imagine.

Avian Entanglements

The first enclosure we encounter is the flamingo den. I see them first out of the corner of my eye, standing tall amidst lush vegetation. It is a picturesque scene and I am shocked to see a family walking among them; a small child, pointing in wonder, his parents standing behind him … the father in a tailcoat and the mother resplendent in a Victorian dress and bonnet? These are not the flamingos I have been looking for; I have been fooled, having mistaken a painted board arching halfway across the enclosure for the real thing. The ‘other’ flamingos sit on the other side of the central pond, facing the billboard. They seem fragile, huddling together for warmth – frail counterparts to their simulacrum ancestors frozen in the Caribbean past. The scene indeed has the tranquillity of a still life; broken suddenly when a duck intrudes into the enclosure, blithely ignoring the sign titled ‘No Touching!’ and careening into the mob amidst a flurry of pink. The birds in the Victorian menagerie across the water remain undisturbed.

I walked across the main path of Artis Zoo to the central bird ‘enclosure’ – bracketed because it is only enclosed on the horizontal axis. When it comes to verticality, the sky is the limit. My experience here was marked by the inability to distinguish between what birds were on ‘display’ – i.e., native to the zoo – and which birds had entered the open enclosure via way of Amsterdam city. Clearly, the charismatic pink-backed pelicans were part of the ‘exhibition’, while the Eurasian Magpies and common gulls were intruders from outside the zoo. But what of the herons who appeared to have constructed nests in the tree branches sitting high above the water? What about the cormorants diving for fish in the depths of the pond?

The most aesthetically eye-catching species on display, the pelicans sat preening their feathers on a central moat. In the Romantic movement, a proper landscape exists with a foreground, mid-ground, and background. From my perspective, the pelicans wandered aimlessly around the mid-ground, with the pond in the foreground and an artificial rock formation rising behind their nests. The enclosure is a testament to the zoo as art gallery. Carl Hagenbeck became the first to apply this idea to zoo design, resulting in the birth of the ‘barless’ (or moated) exhibit (Rothfels 46). The highly aestheticised enclosure at Artis recalls John Berger’s famous proclamation: ‘Everywhere animals disappear. In zoos they constitute the living monument to their own disappearance’ (26). Nevertheless, the fact that the open enclosure does not exclude the possibility of multispecies encounters, including human-animal contact, seems to complicate Berger’s suggestion that the look between animal and human, to which zoos are a monument, ‘is now irredeemable’ (28).

I counted eight species in the pond; pink-backed pelicans (Pelecanus rufescens), common gulls (Larus canus), grey herons (Ardea cinerea), great cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo), Eurasian magpies (Pica pica), coots (Fulica), common goldeneyes (Bucephala clangula), and Eurasian teal ducks (Anas crecca). However, there were only descriptions along the edge of the enclosure for two: the pelicans and the cormorants. The other birds seem to have been drawn to the site by the oilseed crops spilling over the bird feeders positioned throughout the enclosure. It was, in fact, the herons who were the most entrancing. They walked along the paths beside the other visitors, unafraid of human contact. One hopped onto the handrail of the neighboring bridge, regarding me with roving eyes and following me away from the pond as I wandered through the lemur exhibit: an ‘unspeaking companionship’ (Berger 5).

A space of multispecies entanglements; a dead fish floats on the surface of the pond, picked at for a time by a cormorant and then swallowed by an eager pelican. A community of the living and the dead. In their messy coming together, with divergent and overlapping durations and possibilities, this site echoed elements of Thom Van Dooren’s Flight Ways. For Van Dooren, this period of massive ecological loss requires more than respect for any individual species. It is also about acknowledging the ‘myriad lineages that together form our entangled multispecies community’ (41). The central bird enclosure at Artis speaks to the way in which the multiple and diverse flight ways that constitute Earth’s diversity are delicately interwoven with one another. The cormorants diving in the pond for fish, the herons clearing leaves and twigs from the pelicans’ moat, are not flight ways through an empty void, but an entangled way of life, bound up in and becoming as part of a specific multispecies community.

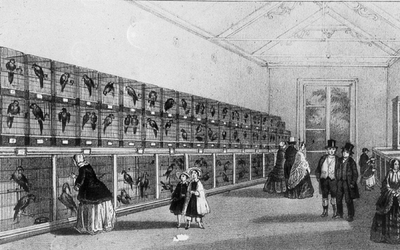

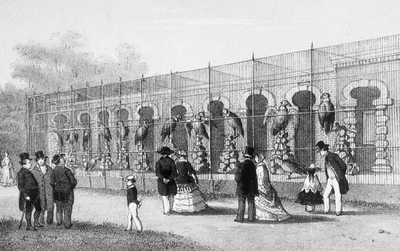

The person most central to the founding and later development of the Amsterdam Zoo was Gerardus F. Westerman – an avid bird lover. In 1838, Westerman mobilized two friends – the watchmaker J.J. Wijsmuller and the broker J.W.H. Werleman – to purchase cooperatively a small tract of land and to co-found a zoological society (Mehos 23). They drafted a brief prospectus and circulated it among prominent members of Amsterdam society. Their stated ambition was to acquire a ‘collection of exotic birds […] both living and stuffed’ (23). When Westerman founded Artis, his own collection of living birds comprised the first animals displayed at the zoo. He performed a great deal of ornithological research, and early prints of Artis show that the birds were housed in small, individual cages – mirroring the ‘scientific zoo’ in London that had inspired Westerman (24).

In contrast, the bird enclosure I visited in Artis Zoo on March 23, 2018, foregrounded multispecies entanglement and human-animal contact. The coots diving to the bottom of the pond bring up trails of weed that nourish the ducks waiting on the banks. And so there is an important sense in which species also carry one another, or as Van Dooren puts it: ‘…nourishing and being co-shaped as members of a particular entangled community of life’ (42). The enclosure seemed to mark a ‘borderland’ of urban/rural/wild areas – ‘conceived as shared and contested living areas and habitats […] interpenetrating forms of species life’ (Chrulew 178). It was, for me, the most interesting space within Artis Zoo; it seemed to refuse the dualism of wilderness and the urban, of freedom and captivity.

Works Cited

Berger, John. “Why Look at Animals?” About Looking. Writers and Readers Publishing, 1980, pp. 1-28.

Chrulew, Matthew. “From Zoo to Zoöpolis : Effectively Enacting Eden.” Metamorphoses of the Zoo: Animal Encounter after Noah, by Ralph R. Acampora, Lexington Books, 2010.

Chutchawanjumrat, Thorfun. “The Zoological Paradox: Reimagining Zoo Architecture,” SURFACE, 2015, pp. 1-94.

Fabregas, Mara C., et al. “Do Naturalistic Enclosures Provide Suitable Environments for Zoo Animals?” Zoo Biology, vol. 31, no. 3, 2011, pp. 362–373.

Horsfield, Thomas. A Catalogue of the Mammalia in the Museum of the Hon. East-India Company (1852), Reink, 2017.

Mehos, Donna C. Science and Culture for Members Only: the Amsterdam Zoo Artis in the Nineteenth Century. Amsterdam University Press, 2006.

Massumi, Brian. What Animals Teach Us about Politics. Duke University Press, 2014.

Pennant, Thomas. History of Quadrupeds. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Rilke, Rainer Maria, and Stephen Mitchell. Ahead of All Parting: the Selected Poetry and Prose of Rainer Maria Rilke. Modern Library, 1995.

Rothfels, Nigel. Savages and Beasts: the Birth of the Modern Zoo. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012.

Van Dooren, Thom. Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction. Columbia University Press, 2014.