Thick descriptions

Unrelating at Artis

By Roos Brands.

It is 13:45 when we arrive at the entrance of Artis on 23 March 2018. With a thick pack of clouds overhead and a temperature of 5°C, Chih-Hen, Eamonn and I shiver with our tickets ready on our phones as we wait for Tess to get a discount with her UvA student card. Is this arrangement part of the zoo’s nineteenth-century Enlightenment heritage? Artis—short for natura artis magistra “nature is the teacher of art and science”—was established in 1838, one of the many zoos founded throughout Europe after the Zoological Garden of London first opened its doors to the members of the Zoological Club of the Linnaean Society of London ten years earlier. Contrary to the private collections of exotic animals kept in menageries during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the primary aim of the nineteenth-century zoo was to educate and enlighten the public. Artis anno 2018 still prides itself on this scientific orientation. Spectacles such as dancing bears and elephant rides were organised up until the 1960s, but entertainment has now made way for public enlightenment in the form of seminars and lecture courses organised at the Artis Academy. In 2009 the Artis endowed chair of Culture, Landscape and Nature was established at the Humanities faculty of the UvA. According to the UvA news item announcing his appointment “Artis Professor” Erik de Jong investigates the interconnectedness of nature and culture in terms of “heritage” and “stewardship.” In November last year microbiologist Remco Kort was appointed a similar position at the VU (VU news item, n.p.).

It is 13:45 when we arrive at the entrance of Artis on 23 March 2018. With a thick pack of clouds overhead and a temperature of 5°C, Chih-Hen, Eamonn and I shiver with our tickets ready on our phones as we wait for Tess to get a discount with her UvA student card. Is this arrangement part of the zoo’s nineteenth-century Enlightenment heritage? Artis—short for natura artis magistra “nature is the teacher of art and science”—was established in 1838, one of the many zoos founded throughout Europe after the Zoological Garden of London first opened its doors to the members of the Zoological Club of the Linnaean Society of London ten years earlier. Contrary to the private collections of exotic animals kept in menageries during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the primary aim of the nineteenth-century zoo was to educate and enlighten the public. Artis anno 2018 still prides itself on this scientific orientation. Spectacles such as dancing bears and elephant rides were organised up until the 1960s, but entertainment has now made way for public enlightenment in the form of seminars and lecture courses organised at the Artis Academy. In 2009 the Artis endowed chair of Culture, Landscape and Nature was established at the Humanities faculty of the UvA. According to the UvA news item announcing his appointment “Artis Professor” Erik de Jong investigates the interconnectedness of nature and culture in terms of “heritage” and “stewardship.” In November last year microbiologist Remco Kort was appointed a similar position at the VU (VU news item, n.p.).

Do De Jong and Kort send their students on field trips to Artis? Perhaps. But Tess is not one of them, and the lady behind the counter is strict: no proof of enrolment at an Amsterdam institution of higher education, no discount. As Tess buys a regular ticket hordes of school children swarm past us toward the exit of the park. We chat with some of them. When asked which animals they have seen, a trio of seven-year-olds shouts in enthusiastic reply: “Ostriches!” When we ask what is so special about ostriches—aren’t they in every children’s farm?—they nod but seem unconvinced that this compromises their interest. After thinking for a while, they add that they also saw donkeys. Another silence. And small monkeys. The girl seems to want to say something more about the monkeys, but then the three are swept away by a seemingly exasperated mother eager to get home. Tess returns with her ticket, most of the children have left and we—still shivering—are ready to enter a deserted, desolate zoo.

Thick Description

A note on methodology before we go through the gates. Written in the context of the NWO project Reading Zoos in the Age of the Anthropocene, this account of our zoo visit aims to record my on-site observations and tease out of these some of the cultural practices that surround the human-animal encounters for which we go—in flocks, on any day of the year, all over the world—to the zoo. The character of this text is therefore as interpretative as it is descriptive. In the words of Clifford Geertz, “thick description” as opposed to “thin description,” which records events and behaviours without construing their cultural import (7). For Geertz empirical observation and theoretical interpretation go hand in hand: “In ethnography, the office of theory is to provide a vocabulary in which what symbolic action has to say about itself—that is, about the role of culture in human life—can be expressed” (27). In other words, the aim of interpreting concrete events and behaviours with the help of a theoretical framework is to outline the underlying cultural practices and determine the way in which these act in the world. Culture is a web of significance, “a public code” (6) with reference to which the individual gesture or “symbolic action” (10) becomes intelligible and meaningful to the interacting subjects. In the observations that follow I will make use of the theoretical reflections about human-animal encounters by Brian Massumi to draw out the cultural ground and import of the symbolic gestures I observed on that grey afternoon in March: In their occurrence and through their agency, what was getting said? (cf. Geertz 10). What cultural webs of meaning are at work in places like Artis? Perhaps it is good to conclude this methodological note by emphasising that this descriptive-interpretative account is an imaginative act. Just as a work of literary interpretation tells a story about a literary text in which that text is made to speak, and thereby participates to some extent in the fictional character of the literary work, so my descriptions and interpretations are fictions in that they are something made, something constructed; the original meaning of fictio, as Geertz points out (15). Rather than fact-finding, for Geerts “anthropological interpretation is constructing a reading of what happens” (18; my emphasis). In a similar vein, the ensuing reading of Artis seeks to contribute not bare facts but rather a narrative-interpretative description of the cultural practices at work in this zoo.

“Dad, what is that?”

We enter. It is 14:05 and Tess and I rush to the lions’ feeding and keeper talk, while Chih-Hen and Eamonn wander off in another direction. Phone calls and emails to three different zoos with the request to interview an employee or look behind the scenes were refused the previous week. The Artis employee answering the phone informed me

We enter. It is 14:05 and Tess and I rush to the lions’ feeding and keeper talk, while Chih-Hen and Eamonn wander off in another direction. Phone calls and emails to three different zoos with the request to interview an employee or look behind the scenes were refused the previous week. The Artis employee answering the phone informed me  in a tired voice that the zoo receives many such requests—too many to grant any; “we are all busy looking after the animals, you know.” So we intend to make the most of the keeper talks. On our list are the lions at 14:15, the vultures at 14:45 and the penguins at 15:15. It is 14:10 when we reach the lions enclosure, where two keepers are busy attaching pieces of meat to

in a tired voice that the zoo receives many such requests—too many to grant any; “we are all busy looking after the animals, you know.” So we intend to make the most of the keeper talks. On our list are the lions at 14:15, the vultures at 14:45 and the penguins at 15:15. It is 14:10 when we reach the lions enclosure, where two keepers are busy attaching pieces of meat to  large metal hooks on trees and walls at a height of about two meters.

large metal hooks on trees and walls at a height of about two meters.

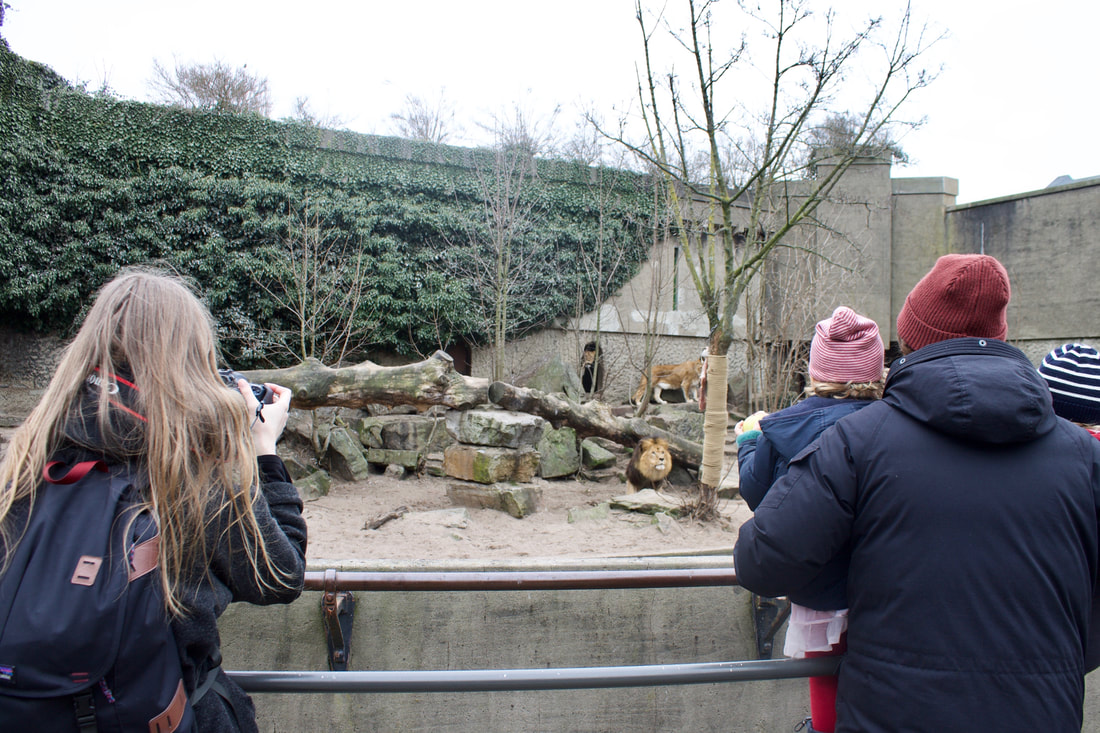

When they have finished and exited the enclosure, the doors separating the outdoor enclosure from the indoor cage are opened with a hidden block and tackle system, and the lions enter the enclosure. There is some excitement, mainly among the adult members of the audience, at the sight of the impressive animals. A father with two children—around two and four years old—stands to our right. The four-year-old boy asks, pointing to the meat: “Dad, what is that?” The father answers: “Meat.” Boy: “No, I mean what kind of animal is that?” Father, in a flatter tone of voice: “O, I don’t know. Perhaps a goat.” While I pen down this short dialogue they continue to speculate whether the pieces of meat are not too big to be goat. I wonder at the father’s striking change in tone from enthusiastically instructive to dull. It seems that the boy’s rephrased question is somehow not the right question to ask. What is the difference between the two? The first question—“what is that?”—in the father’s ears anticipates an object. Or, rather, a category of objects: meat as a commodity produced and sold as animal feed in an industry far removed from the lifeworld of these individuals. The second, rephrased question anticipates a species, a category of living beings. This is the wrong question. At the risk of overanalysing it, I would venture that the ensuing conversation is more animated because it accommodates both premises; flesh as meat-object and as body-of-deceased-individual. The father is more interested in the question of the size of goats, while the child asks such questions as “Do lions like the taste of goats?” The father is concerned with verification: Can I show this or that statement to be true in view of what I know with certainty about goats and these pieces of meat? The child is interested in no such thing. He is busy imagining himself into the individual animals before his eyes. Who is being torn into pieces by those fangs? Is the lion enjoying its meal? What does it taste like?

The Kerbert Terrace. Photo: Paul Paris, 2002.

Pretty as a picture

Brian Massumi’s theory of play at the zoo helps to identify the cultural web of signification that underlies the father and son’s different modes of response to the feeding lions. Massumi identifies the zoo as one of the “contexts where humans work to hold themselves at a distance in the role of unimplicated observer [by means] of a rigidly exclusionary operation” (65). The distinction between humans and animals—who are excluded from the human community—is enforced through the way in which the encounter between zoo inhabitants and visitors is structured visually and logically. The animals are framed as objects laid out to be surveyed by the detached gaze of the human visitor. Massumi observes that in the zoo animals are put “on display as essentially visual figures” (66). This is especially noticeable in the design of the Artis lions enclosure. The “Kerbert terrace,” named after the second Artis director dr. C Kerbert (1890-1927), was built in 1927 and was made a national monument in 2002 (Rijksdienst). A terrace of white sand slopes down toward the visitors, who are separated from the animals by a concrete parapet and a moat. Behind the terrace towers a vast architectural structure reminiscent of an ancient Egyptian temple. A strategically-placed tree trunk encourages the lions to rest in a leisurely position visitors are likely to recognise from nature documentaries. Today the lions choose instead to huddle together in one of the shallow cavities at the back of the enclosure, which from the visitors’ perspective produces, regardless of the dreary weather, an exotic scene. Pretty as a picture. The downward sloping ground, the rocks at the back of the enclosure and the resting places all seem designed to create a picturesque visual effect.

This visual framing also imposes a logical structure. Massumi writes that the “zoo-ological framing instructs the viewer that the premises obtaining for the animal should not be extended to the human surroundings” (66). The premises inside the enclosure are displayed as “nature,” while the immediate surroundings are marked “culture.” A fragment of wilderness embedded in human territory. The human-animal encounter inscribed in this structure is essentially a non-encounter: Like the artistic or scientifically-minded members of the nineteenth-century zoological societies, the contemporary zoo visitor is cued to experience this scene as their detached observation of animals going about their business as if the human observer were non-existent. This notion comes through in the keeper’s casual comments on the lions’ habits and relationships with one another. Standing behind the visitors who are watching the lions have their meal, he explains through a microphone that the food is tied up so as to stimulate a naturalistic effort to obtain food. Because in the wild lions only hunt occasionally, they get large pieces of meat only once a day, and fast on Thursdays. My confusion at this statement—the pieces of meat seem quite small to me and don’t lions hunt only once a week?—is soon resolved. The keeper says, in seeming contradiction with his earlier statement, that in Artis the lions are fed smaller portions and more often than in the wild. I assume this arrangement is popular with the visitors: the feeding has drawn quite a crowd.

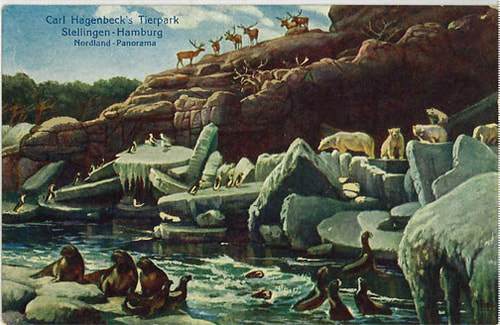

A postcard depicting the “Frei-Anlagen” of the Hagenbeck zoo.

The tension between animals’ and visitors’ interests becomes even more prominent when someone asks why the doors to the indoors cage have closed. With a chuckle the keeper replies that since the indoors shelter is heated, the lions would race back inside after grabbing the meat. They would be invisible to the public “and you would complain about not getting value for your money.” Remembering the frostwork on the windows of my home in January, I wonder how the lions bore it. On the savannah temperatures rarely drop below 18°C. Artis is open 365 days a year. The keeper tells about the construction of a new, heated glass cage where the lions can be visible and warm at the same time. Until it is completed we, apparently, demand our money’s worth and they will have to shiver it out. Two different webs of significance render the practice of exhibiting lions meaningful to the human individuals: the attempt to simulate a state of wilderness and the effort to create an attractive spectacle for the visitor. A third one is implicit in the keeper’s comments on Caesar, the ageing patriarch of the pride. In the wild, the keeper explains, this “elderly gentleman” would have been deposed by a younger male long ago. “But here in Artis we spare him the fight.” Caesar’s unusual longevity in captivity is presented as an Edenic state superior to the wild. This notion has a rich cultural history: It connects Edenic simulations of peacefully cohabitating wild animals (cf. Isaiah 11:6) in the Hagenbeck Tiergarten at the beginning of the twentieth century to contemporary conceptions of the zoo as a Noah’s-arc-style means to prevent the extinction of endangered species. The Artis website notes that the so-called “Frei-Anlagen”—“seemingly natural enclosures with as few bars and wire as possible”—of Carl Hagenbeck’s zoo near Hamburg were a source of inspiration for the Kerbert Terrace (online).

Child’s play

So far, so good. But what does all this tell us about the father, the son, the lion and the goat? Massumi observes that children have not yet fully assimilated the visual-logical framings of animal-human, object-subject and nature-culture than adults, and are therefore often less able to “unsee the singularity of the animal” (73). Unlike their parents, children are swept up in a playful imaginary affective encounter with the animal that is awake to their singularity and the relationality of the situation. This is, I think what we saw at work in the father-son dialogue. The child was affectively-imaginatively involved with the singular being before his eyes, while the father only experienced displayed objects in a sterile non-encounter. Perhaps his change in tone served (unwittingly, of course) to condition the child to enter into the non-relationship that is the accepted manner of (un)relating to animals in the zoo.

The anatomy of cuteness

How skilled some adults are at unrelating to animals at the zoo becomes evident when Tess and I pass the elephant enclosure that opened in June last year. A mature cow and a calf stand near the gate leading to the indoors shelter. For the entire time we spend there, the cow is pushing her trunk through the bars of the gate and pushing against it. The calf is stumbling over a ball by her side. Five middle-aged ladies carry on a conversation about the animals’ behaviour. Topic number one is the cuteness of the calf. Dutch schattig “cute” occurs more often than any other significant word in my transcript of the dialogue. If this appears to signal affect and relationality, it does so only on the surface. Massumi writes that “sentimentality reflects the relational content back onto the individual” (79). It designates affect not as relational but as the attribute of an autonomous subject: “as something each individual has inside itself, as a function of its particular point of view on the situation” (79). The notion of point of view implies the detached-subject-observing-inert-object structure I discussed above with reference to the lions and father. In terms of the elephant-lady encounter, the calf has very little say in the cuteness at play here. It is an affective experience enclosed within the human visitors, and could equally apply to a painting, a piece of furniture, or any lifeless object. This is the way sentimentality renders the calf as well: as an object with perceptible properties, never as a singular individual with whom one could enter into a social relationship. This “reading” is in line with the ladies’ interpretation of the cow’s behaviour. They are of the opinion that she is pushing against the gate because she is fed there at this time every day and is therefore instinctively “programmed” to act in this way. Ivan Pavlov is still among us. Elephants are living machines.

How skilled some adults are at unrelating to animals at the zoo becomes evident when Tess and I pass the elephant enclosure that opened in June last year. A mature cow and a calf stand near the gate leading to the indoors shelter. For the entire time we spend there, the cow is pushing her trunk through the bars of the gate and pushing against it. The calf is stumbling over a ball by her side. Five middle-aged ladies carry on a conversation about the animals’ behaviour. Topic number one is the cuteness of the calf. Dutch schattig “cute” occurs more often than any other significant word in my transcript of the dialogue. If this appears to signal affect and relationality, it does so only on the surface. Massumi writes that “sentimentality reflects the relational content back onto the individual” (79). It designates affect not as relational but as the attribute of an autonomous subject: “as something each individual has inside itself, as a function of its particular point of view on the situation” (79). The notion of point of view implies the detached-subject-observing-inert-object structure I discussed above with reference to the lions and father. In terms of the elephant-lady encounter, the calf has very little say in the cuteness at play here. It is an affective experience enclosed within the human visitors, and could equally apply to a painting, a piece of furniture, or any lifeless object. This is the way sentimentality renders the calf as well: as an object with perceptible properties, never as a singular individual with whom one could enter into a social relationship. This “reading” is in line with the ladies’ interpretation of the cow’s behaviour. They are of the opinion that she is pushing against the gate because she is fed there at this time every day and is therefore instinctively “programmed” to act in this way. Ivan Pavlov is still among us. Elephants are living machines.

The ladies leave. There is no feeding session on the schedule, no keeper arrives. The cow never stops thrusting her trunk between the massive bars. The calf stumbles over the ball and falls against her mother. Is the indoors shelter warm? Tess and I wonder. “Designed for elephants,” is the title of the Artis webpage on the “objects for behaviour enrichment” placed in the elephant enclosure. The Asian Elephant is native to regions with an average temperature of 30°C. How do you mean, “designed for elephants”? Even in the newest, most state-of-the-art enclosure of Artis visibility seems detrimental to the animals’ wellbeing.

The ladies leave. There is no feeding session on the schedule, no keeper arrives. The cow never stops thrusting her trunk between the massive bars. The calf stumbles over the ball and falls against her mother. Is the indoors shelter warm? Tess and I wonder. “Designed for elephants,” is the title of the Artis webpage on the “objects for behaviour enrichment” placed in the elephant enclosure. The Asian Elephant is native to regions with an average temperature of 30°C. How do you mean, “designed for elephants”? Even in the newest, most state-of-the-art enclosure of Artis visibility seems detrimental to the animals’ wellbeing.

Why I could not write about the subject of this essay

In bringing these observations to an end, I became aware that they are more about my encounters with the visitors rather than with the inhabitants of the zoo. This is certainly but not only for the reason that, as John Berger put it, the zoo “is, in fact, a monument to the impossibility of such encounters” (21). Due to the zoo’s visual-logical structuring of the human-animal contact as subject-observing-object it is very difficult to enter into a singular relationship with a zoo inhabitant. This is, however, not the only reason for the marginality of the animals in my report. The fact is that when we looked each other in the eye my horror and shame at the bars between us were so great that all words disappeared.

Left: The last drawing I made using an Artis membership bought for that purpose in 2016. The lemur and I stared at each other for a long while before I resolved never to set foot in a zoo again. Above: The last picture I took on our trip, returning to my earlier resolve.

References

Berger, John. “Why Look at Animals?” About Looking.

Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures. Selected Essays. New York: Basic Books, 1973.

Massumi, Brian. What Animals Teach Us About Politics. Durham and London: Duke UP, 2014.