Thick descriptions

The Disconnect Between Education and Entertainment at Blijdorp Zoo

By Lauren Hoogen Stoevenbeld.

There is something strange going on when a research project becomes almost like a school trip. Upon hearing that three of my fellow students and I were going to visit a zoo to do research, my friends wished us a nice day and said they hoped we would have sunny weather, which I do not think they would have done had we been going to an archive or a museum instead. And we, as researchers, too were excited for our excursion. Although we came to the zoo with research questions, we were also happy that we would be able to see the baby rhino that had been born only a month before. Even before entering the zoo, this demonstrated how a zoo resists becoming a site of education rather than just entertainment.

But why study zoos at all? What did I hope to find out during my visit to Diergaarde Blijdorp, the zoo of Rotterdam, on 31 March 2017? The relationship between humans and nature has changed drastically over the last hundred years, a period that has come to be called the “Anthropocene.” The Anthropocene is our current geological period, in which humans have become the primary Earth-shaping force through our rapidly expanding industrialization, population growth, and nuclear warfare. Citizens of Western countries are hardly in contact with nature anymore, let alone with wild animals. The zoo has become one of the primary sites in which the relation between humans and nature is played out. In line with the Anthropocene, zoos have shifted their focus from displaying animals just for show, to sites of education and conservation, as shown by Eric Baratay and Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier, to counter the negative effects of human influence on the earth. Although the zoo is now one of the few places where ordinary Europeans can encounter “the wild,” critic John Berger has famously argued that it is not possible to engage with wild animals at the zoo. First of all, he writes, they are no longer wild and second, they do not look back, preventing the meaningful relationships that humans and animals once had. Even if we cannot actually look at animals in the zoo, we can still look at the zoo itself instead, as an artificial nature-construct, to see how the relationship between humans and animals is represented there and see how the zoo relates to the Anthropocene problems like climate change and mass extinction.

A second reason for my study of the zoo is Joseph Keulartz’ article “Ethics at the Zoo” in which he sketches a highly optimistic image of the changing function of zoos, stating that “zoos are currently in the process of transition from venues of outdoor public education and entertainment to fully-fledged conservation centers.” He also thinks that zoos can activate their visitors to contribute to wildlife conservation. Since this was not in concordance with my experiences in various zoos in the Netherlands and since I am aware of the problems of zoo conservation programs, as presented by scholars like Baratay and Hardouin-Fugier, I was sceptical of this. I decided therefore to study the representation of extinction and conservation in Diergaarde Blijdorp. In this paper I will show that, although Blijdorp provides much information about their own breeding programs and their support of conservation projects in the wild, there is a disconnect between the wish the spread this information and the visitor. Diergaarde Blijdorp is the most popular zoo in the Netherlands with 1,5 million visitors a year. It is accredited by the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria and takes part in the European Endangered Species Program. It has both old monumental parts and recent additions, which illustrate the changes in the goals of zoos over the past eighty years. This makes it an interesting and representative case study. I present my research in the form of a thick description, a method used in anthropology. This has the advantage that it provides the reader with meaning instead of just a dry factual description. Meaning is created based on the contexts of the case study, which are also taken up in the description. The pictures I have included will further strengthen my claims and will illustrate to my reader to what extent Blijdorp really “is” nature conservation, as is stated on the back of their visitors’ map.

A History of Diergaarde Blijdorp: From a Human Towards an Animal focus

Diergaarde Blijdorp opened in 1940. Its predecessor, the Rotterdamsche Diergaarde had to move out of the city centre of Rotterdam, where it had been founded in 1856, in favour of a housing project. In 1937 the building of a new zoo at the northern edge of the city started and the zoo was renamed after its new neighbourhood, Blijdorp. Because Rotterdam was bombed on 14 May 1940 by Nazi Germany, the surviving animals—many had died—moved into the new zoo earlier than expected. The design of Diergaarde Blijdorp was in the hands of Dutch architect Sybold van Ravesteyn. He made Blijdorp into one of the first zoos with one overarching design. Van Ravesteyn wanted his design to be not just functional but mainly aesthetically pleasing. Although the animal enclosures were also part of his design, he pushed the animals to the background: “Maar toch speelden dieren niet de hoofdrol in zijn ontwerp. Alles draaide om de schoonheid van de architectuur; dieren waren slechts de figuranten in dit ‘sprookjesachtige’decor” (Alderlieste 9).

Like the famous menagerie of Versailles, Van Ravesteyn’s design for Blijdorp was symmetrical and had a watching tower in the middle, placing the human literally at the centre of a harmonious imagination of nature (De Jong 75). The tower was demolished in 1972 because it had become dilapidated, but there has been talk of rebuilding it (“Uitkijktoren”). Van Ravesteyn was also inspired by German zoo designer Carl Hagenbeck who opened his groundbreaking Stellingen zoo in Hamburg in 1907. His style is characterized by the use of deep ditches to enclose animals instead of fences and placing them in seemingly natural environments (Baratay and Hardouin-Fugier 237-38).

The Rivièra Hall, symmetric axis of Van Ravesteyn’s design.

Detail of Van Ravesteyn’s giraffe house.

Although most of Van Ravesteyn’s buildings are still in use, their functions have changed to housing for smaller animals and restaurants because they are not in line with modern standards for keeping animals. Furthermore, many new, more animal friendly enclosures have been added. An example of this is the giraffe enclosure. The giraffes used to live in one of Van Ravesteyn’s buildings, but now have a much larger indoor enclosure and an outdoor enclosure they share with the kudus, right next to the zebras and the ostriches. These enclosures together form a large savannah area. This new building style is in line with the zoo’s main goal: “Diergaarde Blijdorp wil op bescheiden wijze bijdragen aan de instandhouding van de aarde, door een brede collectie dieren op verantwoorde en inspirerende wijze te tonen aan het publiek, met als doel om de bezoekers zich bewust te maken van de diversiteit op aarde, zodat zij zich zelf actief gaan inzetten om deze aarde te beschermen” (Beleidsplan 2).

Not only are the new enclosures more animal friendly, they also give the visitors a better insight into the animals’ natural habitats by making the difference between the zoo and the wild seem smaller. To develop this goal further, a whole new area was added to the zoo in 2000, on the other side of the railroad that now divides the park in two. The main attraction here is the Oceanium, a large building that takes the visitor along different coastal areas with a combination of aquariums and land animals like snakes, turtles, and penguins. A new entrance to the zoo was also made here, with a big parking lot. Most visitors enter through here and thus walk through the zoo from new to old. The old entrance that was designed by Van Ravesteyn is still in use, but is hard to access by car and is thus not used as much.

Cutout of Bokito the gorilla with a box for donations.

The inside of the new giraffe house with the “savannah” in the background.

Reading Signs: Breeding and Protection Programs

As I arrived by train, I entered the zoo via the historical entrance. Upon entering the zoo, visitors stand face to face with a cutout of Blijdorp’s celebrity gorilla Bokito, urging them to donate their old mobile phones to help him and his family.2 The apes of Blijdorp are made into characters of a larger story about endangered gorillas in the wild. Telling stories is a common way for humans to deal with extinction, more so than scientific discourses. as has been argued by scholars like Ursula Heise and Thom van Dooren. Not only do stories provide an outlet for grief, but, moreover, when these stories appeal to emotions they can work as a catalyser for action (Heise 23). Making Bokito into a likeable character—his attack is downplayed and elsewhere he is called a “family man” and a good leader—might make visitors feel bad about wild gorillas and drive them to helping. The plea to donate old phones is repeated in more detail on signs next to the gorillas’ outdoor area and inside the ape house, their indoor quarters. Visitors are also told: “Jane [Goodall] is looking for your help.” The subsequent posters explain how gorillas and chimpanzees have become endangered and what visitors can do to help solve this problem, as they are told: “Your efforts count.”

Of course, it is not all up to the visitors to protect animals. Blijdorp is part of many international breeding programs, as part of the European Endangered Species Program (EEP), which is under the supervision of the selective European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). One of the main goals of the EAZA is: “Educating our visitors about animals and their habitats and providing them with the knowledge and opportunities they need to live sustainably as part of nature” (“About us”). Another goal of the EAZA and of Blijdorp too is supporting in situ conservation projects. If an animal at Blijdorp is part of an EEP program, this is usually mentioned on the information signs next to their enclosure. All animals have at least one sign with information of about A3 size, apart from the fish in the Oceanium, which are most only the time only mentioned by name.

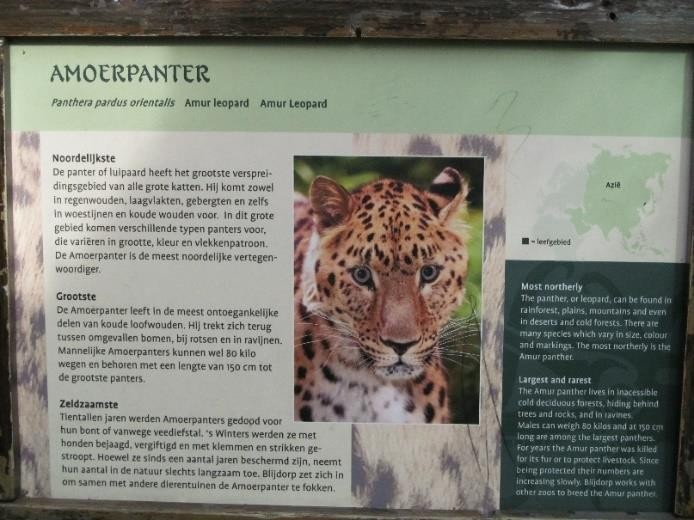

Information sign about the Amur leopard, which Blijdorp breeds.

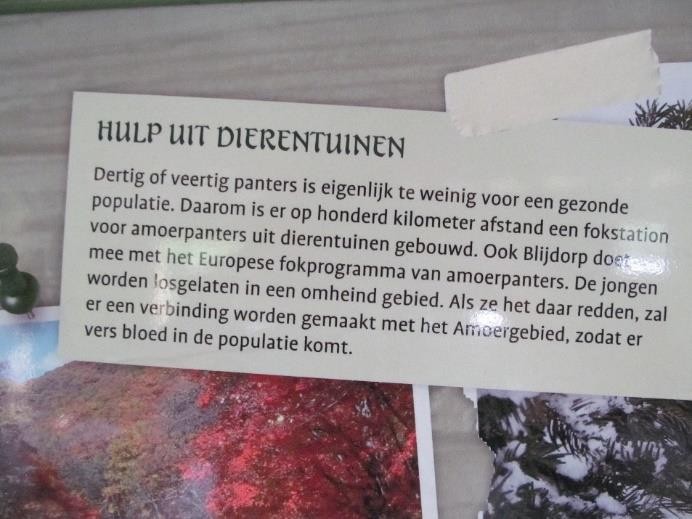

Reintroducing leopards born in captivity into the wild.

Clearly, Blijdorp pays a lot of attention to nature and animal conservation, even more so than I had expected. The park is filled with information about breeding and protection of elephants, okapis, red pandas and many more species. They even make the connection between the zoo and the wild reasonably clear, as in the case of the Amur leopards: “Blijdorp tries to breed Amur leopards to be able to bring them back to the wild.” The rate of success of the breeding programs, however, is only mentioned in few cases. Reintroducing captive animals into the wild can be problematic because they lose wild behaviour and instincts and can even get physically deformed by their conditions of captivity (Baratay and Hardouin- Fugier 272-74). Coincidentally (?), mainly the successful cases of reintroduction, like the storks and the hornbills, are mentioned, not the animals that are experiencing more difficulties.

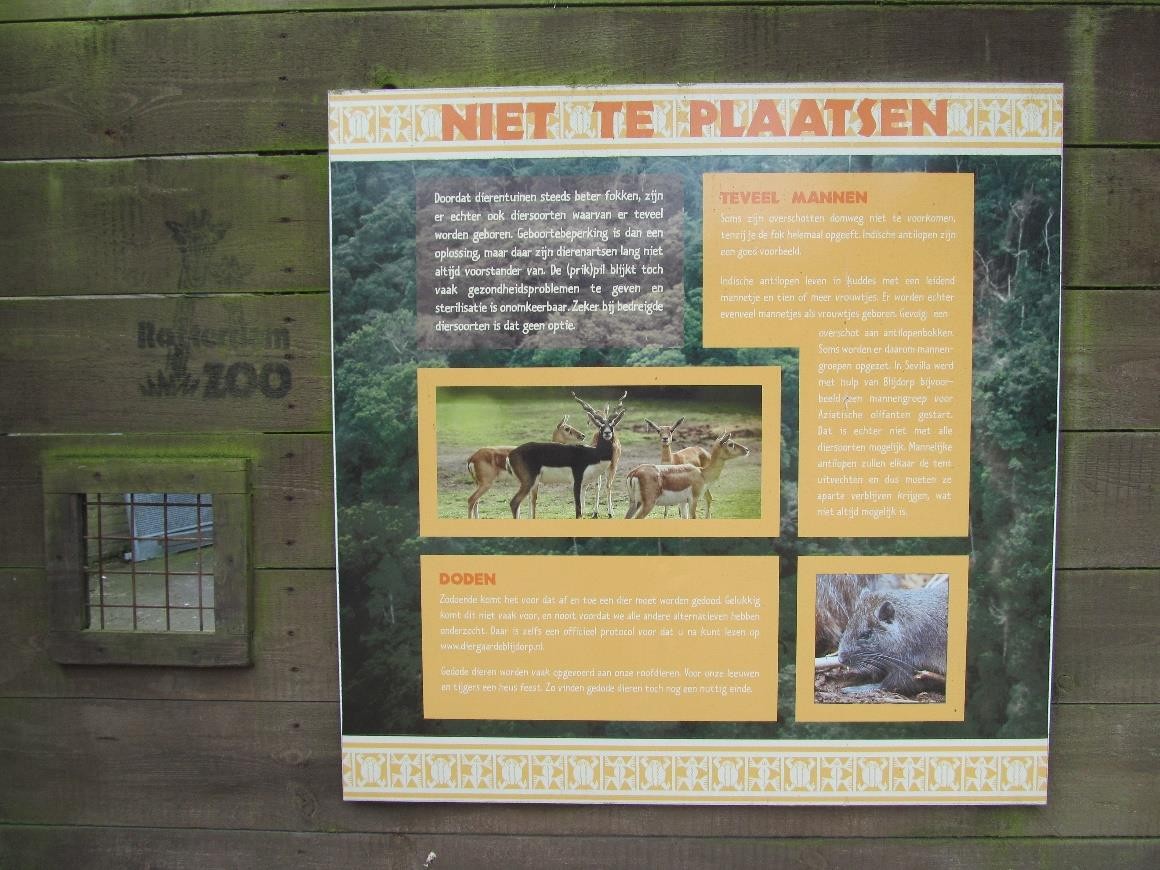

What is done with the surplus animals that cannot be placed in other zoos.

While they could be more open about this, Blijdorp is transparent about their policy when it comes to surplus animals. As cultural scholar Matthew Chrulew points out, this is one of the many problematic aspects of breeding animals, in which the unequal power relation between humans and animals becomes clear. Individual animals that are considered “genetically irrelevant” are sometimes killed for the sake of the rest of their species, a paradoxical “care for life” (Chrulew 150). In a series of three large signs (see figure 7 for the third one), Blijdorp explains their surplus policy. Hundreds of animals are born in Blijdorp every year. In the wild, these animals would leave their parents once they are mature. That means they must find another place for these animals, especially for the males who can cause conflicts in groups. They are kept temporarily in enclosures behind the scenes. Often they are eventually taken in by other zoos, but in rare cases it happens that animals are killed, Blijdorp states, and fed to the predators. Visitors are invited to read the official protocol for this on the website (which, unfortunately, I have not been able to find). This is sensitive information, as killing animals in the zoo can lead to strong reactions, as was shown when Kopenhagen Zoo decided to feed a surplus giraffe to the lions (Eriksen and Kennedy). It must have been a conscious decision to disclose this information to the public, but the other visitors seemed uninterested and rather focussed on the zebras on the opposite side of the path.

Cooperation with other foundations.

That Blijdorp hopes their visitors read all the signs becomes clear again in and around the Oceanium. Like the sign of Bokito near the entrance, these signs are meant to activate the visitor, only in this case not just to donate but—more drastically—to change their lifestyle. Part of the Oceanium is filled with expositions about sea reservations and other projects to protect the sea in cooperation with various partners like Greenpeace, WWF, and the North Sea foundation and on top of that, visitors are urged to eat sustainable fish, like the sea lions and other carnivorous animals at the Oceanium do. Next door, at the polar bears, tips are giving on how to save energy and fight global warming.

The Bokito Family Game at Blijdorp’s gift shop. Image by Vincent Reijnders.

Paratexts: The Restaurant and the Gift Shop

The activating signs stand in contrast with what I would like to call the “paratexts” of the zoo. The term coined by literary theorist Gérard Genette indicates the elements around a main text, like a blurb, cover, or colophon, that are not part of the main text but do shape the way we see it. If we take the animals, their cages, the visitors, and, in accordance with recent developments, the educational information as main components of the “story” of zoo, then a few other side-components remain, like the restaurants and cafes, the gift shop, and the advertisement campaign, which nevertheless shape the perception of the main “text” and should thus be taken into consideration. The restaurants at Blijdorp do not promote durability and environmentally friendly food. There are few organic and/or vegetarian options. The most prominent items on the menu are fries and classic Dutch deep-fried meat snacks like croquettes and frikandellen. This is not the “fault” of the zoo, but it shows a dissonance between what Blijdorp tries to teach its visitors and what the visitors want. Since the supply is at least in part determined by the demand, it seems that visitors do not make the connection between the conservation message of the zoo and their own daily habits like eating. Apparently, for many visitors there is a big difference between a buffalo or a warthog for looking at and a cow or a pig for eating. The souvenir shop hardly promotes durability either. There are lots of plastic toys. There are no books about threatened species or conservation, only about animals in general or storybooks about animals. There are some stuffed animals of the WWF, of which part of the price goes to them. We encounter Bokito again in the form of a cartoon animal on lunchboxes, jigsaw puzzles, and, along with his entire family, in a Game-of-the-Goose-like board game. The cartoonification of animals indicates a prioritizing of entertainment over education. Berger has even argued that by removing the object’s animality, it becomes a representation of the human, making the human look at itself instead of at the real animal (15- 19), which Blijdorp wants to be the focus of attention.

A group of school children having a break near the lions.

The ape house.

The Visitor: A Species of its Own

The visitors on the average weekday on which I visited Blijdorp consisted mainly of small children with their parents or grandparents. Groups of school children made up the rest. It seemed like most visitors were more occupied with each other than with the animals. Frequently overheard where sentences like: “Can I have a biscuit?” “Is it much further?” “Stop yelling now, or we’ll go home.” “Stop pestering your brother!” and an occasional: “Look mum, I can see its butt!” I rarely overheard people talking about the animals, let alone about the signs next to their cages. There was not much awareness, neither of Blijdorp’s conservation goals nor of the fact that they paradoxically lock animals up to achieve them. Only one little boy of about three years old remarked: “It looks like prison,” when we were standing in the panopticon-like ape house. In contrast, the grown man next to him was laughing at a gorilla because it was eating and pooping at the same time. At the polar bears, most people only had eyes for the one bear that was jumping up against the glass, not noticing the other two who were nervously walking up and down in the background.

Young children can of course not read the texts on signs and the information on them might be difficult to convey for their (grand)parents. Moreover, the information in Blijdorp often placed in opposition to the animals, sometimes behind a wall that hides the animals from view or hidden in a little cabin. As I noticed, people hardly stop to look at the signs. And why would they? People go to the zoo to have a nice day out and look at fun animals. The information supply of the zoo is passive and it hardly invites the visitor to look at it. The visiting school children might be brought closer in touch with educational materials about conservation through various assignments, but it can hardly be expected from children at the zoo to focus on information signs instead of on animals and playgrounds.

Finally, there seems to be a tendency in the development of animal enclosures towards immersion, where the visitors can see the animals all around them or even walk in between them without any fences. In Blijdorp, this is the case with the prairie dogs, the wallabies, the butterflies, and in multiple open aviaries. While it is nice for the visitors to be able to get as close to the animals as possible, the more immersed they are the easier it becomes to ignore the educational information.

Conclusion

Blijdorp may “be” nature conservation, as they claim, but their visitors are consumers of entertainment. This is not necessarily a bad thing, since by buying tickets these people provide the zoo with money for their conservation projects. However, it means that Blijdorp does not fulfil its goal of activating people to contribute to the protection of the Earth as well as they would like. The information about conservation is competing for the visitor’s attention with the animals and the animals win easily. To be clear, I do not propose to close the playgrounds, ban the stuffed animals, and throw out all tasty but unsustainable food. Having fun at the zoo should still be allowed. However, if the attempts at education are not very effective, as I have argued, and education is one of the main goals of the modern zoo, then new attempts should be made at improving this. In this respect, I am thus not convinced by Keulartz’ rose-coloured image of the zoo. A way in which he would be able to convince me is doing a survey of visitor’s experiences of the zoo, something that is unfortunately outside of my expertise, but highly relevant for this study. The tension at the zoo between education and entertainment has been in place since the seventeenth century (Baratay and Hardouin-Fugier 64-65) and we cannot expect it to be solved easily. But education and entertainment do not necessarily have to contradict each other. They can an also go together. A gift shop could sell board games where you have to save animals from poachers or informative picture books about how to become an environmentalist. Restaurants could offer delicious sustainable food and prevent food waste. In fact, my visit to Blijdorp felt rather like a school trip. I had a nice day, although my feelings were probably more conflicted than those of other visitors. I did not donate my old phone to Bokito, nor money. I used up a lot of cheap, unsustainable batteries with my camera. Had I not already been vegetarian (albeit not a very consistent one), I do not think that the demand to eat only MSC certified fish would have had any effect and unlike other visitors I came to Blijdorp especially to study its conservation and environmentalist efforts.

2 In 2007, Bokito escaped from his enclosure and attacked a female visitor, which made the news all over the world (“Vrouw ernstig gewond”). This attracted many new visitors to Blijdorp and Bokito is now one of the flagship animals of the zoo.

Works Cited

“About Us.” European Association of Zoos and Aquaria, 2017, www.eaza.net/about-us/.Accessed 9 Apr. 2017.

Alderlieste, Constance. “Monumentaal Blijdorp: Een Sprookjestuin.” De Giraffe: Magazine van Diergaarde Blijdorp, Fall 2016, pp. 9-11.

Baratay, Eric and Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier. Zoo: A History of Zoological Gardens in the West. Translated by Oliver Welsh, Reaktion, 2002.

“Beleidsplan Diergaarde Blijdorp.” Diergaarde Blijdorp, Dec. 2013, www.diergaardeblijdorp.nl/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Beleidsplan-Diergaarde- Blijdorp-v12-2013.pdf. Accessed 9 Apr. 2017.

Berger, John. “Why Look at Animals?” About Looking, Bloomsbury, 1980, pp. 3-28. Chrulew, Matthew. “Managing Love and Death at the Zoo: The Biopolitics of Endangered Species Preservation.” Australian Humanities Review, no. 50, 2011, pp. 137-57. Dooren, Thom van. Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction. Columbia UP, 2014.

Eriksen, Lars and Maev Kennedy. “Marius the giraffe killed at Copenhagen zoo despite worldwide protests.” The Guardian, 9 Feb. 2014, www.theguardian.com/world/2014/ feb/09/marius-giraffe-killed-copenhagen-zoo-protests. Accessed 10 Apr. 2017.

Genette, Gerard. “Introduction to the Paratext.” New Literary History, translated by Marie Maclean, vol. 22, no. 2, 1991, pp. 261-72.

Heise, Ursula. Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species. U of Chicago P, 2016.

Jong, Eric de. “Waardering en Kritiek.” S. van Ravesteyn. Stichting Architectuurmuseum Amsterdam and Centraal Museum Utrecht, 1977, pp. 64-80.

Keulartz, Joseph. “Ethics of the Zoo.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Environmental Science, Feb. 2017, environmentalscience.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/ 9780199389414.001.0001/acrefore-9780199389414-e-162. Accessed 9 Apr. 2017.

“Uitkijktoren Diergaarde Blijdorp.” Top010, 1 Dec. 2012, www.nieuws.top010.nl/ uitkijktoren-diergaarde-blijdorp.htm. Accessed on 9 Apr. 2017.

“Vrouw ernstig gewond door in Blijdorp ontsnapte gorilla.” De Volkskrant, 18 May 2007, http://www.volkskrant.nl/binnenland/vrouw-ernstig-gewond-door-in-blijdorp- ontsnapte-gorilla~a840599/. Accessed 9 Apr. 2017.