Thick descriptions

‘Special Encounters’: A Thick Description of Blijdorp

By Leonie Brasser.

Introduction

Blijdorp is one of the largest, and with about 1,5 million visitors a year, most popular zoos in the Netherlands. ‘Special Encounters’ is its central slogan and with its own specific history, being ‘the zoo in which Bokito once escaped,’ Blijdorp proved to be very interesting for my research. Since the specialness of an encounter is difficult to measure, I focused on the ways in which Blijdorp aims to bring the animals closer to the visitors. The central question is; what means does Blijdorp employ to bring the animals closer to the visitor, and to what extent and in what way is this done successfully? Due to the centrality of presentation and looking in this paper I will make use of a larger number of pictures than what would usually be expected in academic writings. The idea is to fully engage the reader and invite him or her to look and think along. Furthermore, I will delve into the history and means of presentation of this particular zoo, not to say something interesting only about Blijdorp but in the hope of drawing out its entangled significance and thus to further reveal and think through assumptions and ideas about the animal-human relationship.Whereas my visit was of course inspired and informed by my theoretical background in animal studies, the aim will be to diagnose rather than predict (Geertz, 7). This involves that I will aim to give as elaborate and precise descriptions as possible informed by, rather than reduced to theory. In aiming to give a reading of what happens, the event itself (in this case the zoo itself) should be central since we will not learn anything new from ‘arranging abstracted entities into unified patterns’ (Geertz, 5).

Historical Background

Rotterdam has had a zoo in its city-centre from 1855 on, yet the Blijdrop zoo as we know it today, only officially opened in 1940. In 1937 it was decided that the zoo had to move from the centre of the town. In the year that followed the entire zoo was redeveloped and rebuilt in accordance with architect Ravensteyn’s design. Sybold van Ravensteyn had a particular individual style. The cages he designed were not developed to centralize the animals that inhabited them, the animals merely served to enhance the aesthetics of the cages. Yet, he also incorporated some of the popular ‘Hagenbeck characteristics’; he replaced fences with natural enclosures and the exhibition areas he designed were relatively large.

On the seventh of September 1940 the Zoo Blijdorp was officially opened. Through the decades, the animals have gained a central place and much has been done in order to improve their surroundings and well-being. One specific event that had a large impact on the Blijdorp zoo concerns the temporal escape of the gorilla Bokito. Almost exactly ten years ago on the 18th of may 2007, Bokito jumped the ditch surrounding his outdoor cage. After escaping, Bokito severely wounded a female visitor. He had dragged her over the ground to the canteen nearby where he was eventually overpowered and tranquilized by one of the zookeepers. After the incident the zoo promised to prevent future outbreaks. Signs were placed to refrain visitors from seeking contact and a high wall replaced the ditch. Later it became known that the wounded visitor in question had been a frequent visitor, spending a lot of time in front of Bokito’s cage observing his behavior and hoping to establish some kind of communication. Bokito soon became one of the most famous inhabitants in Rotterdam, and the term ‘Bokitoproof ‘ was judged the most popular word of 2007.

Figure 1.

Hidden in plain sight

To fully research the methods and employments of the zoo in their aim of bringing humans and animals closer together I stepped over lines and visited areas that were strictly speaking only allowed to employees of the zoo. Salih argued in line with Susan Sonntag that in the pictures of animal-suffering we have access to, we should always ask ourselves what is not being shown. Salih showed that pictures of animals in warzones sometimes serve to distract us from other forms of suffering. In a similar way, I was trying to find out what was hidden from view in Blijdorp and what we may induce and learn from this invisibility. Not being the type of person to whom breaking rules and stepping over lines comes quite naturally, I was constantly (somewhat nervously) looking around. Was I being noticed by anyone except from my classmates? What would happen if I got ‘busted’ by one of the zoo-employees or if other visitors would notice (and maybe imitate or condemn) my behavior? Interestingly however and contrary to all expectations I had, no-one seemed to be really interested in what I was doing. At least several visitors saw me but a sideward glance was all my behavior evoked. No one stopped and stared, no questions were asked, no zoo-employees were called. On the face of it, my rebellious behavior was just not that interesting to the other visitors. Another thing that highly intrigued me was how relatively easy it was to enter these ‘hidden’ areas. Any visitor could have done the same; there were no guards, camera’s or simply high-enough fences to ward of any curious visitors like me. Figure 1 shows the path I entered after stepping over a low hanging cord. On the right side of the picture you will find the door to a cage that, at first sight looks very different than other cages you may encounter at the zoo; figure two zooms further in on the cage.

Figure 2.

In his book ‘Zooland: the institution for captivity’ Braverman investigates the working of the gaze in zoos in the United States. In the first chapter he describes the goal of ‘naturalization’ of these zoos. Zoos aim to emerge visitors in an as authentic experience as possible of ‘a wild nature’. Braverman emphasizes that a lot of work is put into arriving at this wild nature. The artificial elements are very well disguised and the lines between authentic and artificial are blurred. On the other hand, Braverman characterizes the zoo’s nature as a ‘humanized nature,’ since it is only as wild as the public wants it to be. ‘Elements that promote a safe and sanitized environment’ are added and predators are not enabled to feed themselves with other animals. However, the lower the place of the animals on the food chain, the greater the chance the public will endorse any animal-eating practices. There is for example no problem in feeding animals dead fish. He concludes that the animals “must comply with the human expectations of their improved humane nature”( Braverman, 37). However, he argues that different rules are applied to the ‘holding places’, cages that are not accessible to the public. In contrast to the exhibition areas, no attempt is made to conceal human traces, they are small and practical and made by technical architects (whereas the exhibition areas are designed by landscape architects).

If we compare the general characteristics of holding places as pointed out by Braverman to the cage in figure 2, we could add that in this cage not much work is done to sanitize the place. The cage is filled with the birds’ excreta, and if I would not have know where to look I could have easily followed my nose. The smell was much stronger in comparison to the cages that are accessible to the public. Indeed, zoos aim at bringing visitors ‘close enough to see but not to smell’ (Braverman, 72).

Figure 3.

Yet if we closely examine the ‘hidden’ cage and compare it to an exhibition area that is similar in size, like the one in figure 3, the difference is not as great as it may seem. You merely have to think away the filling on the floor and the paintings on the walls. Moreover, I don’t think the paintings really help in creating a more wild picture but rather emphasize the artificiality of the cage. Does the cage then fail in immersing the visitor in a wild experience? Or is it something else altogether the visitors want to look at and see when they visit a zoo like Blijdorp? It is important to note here though that the area where the various monkeys are kept is part of the historical centre of the zoo. It is no wonder then that it does not have the Hagenbeck look that is so characteristic for the modern area. Yet the question remains what it may be that catches the visitor’s gaze in the case of such small and artificial cages. We should not only always ask ourselves what is not shown, as if what we see is only something that overcomes us, (some kind of passive receiving) we should also ask what it is that we look at. Why is it that zoo-visitors did not look at the woman stepping into closed off areas and why is it that they don’t seem to recognize or are bothered with the small cages of the historical area?

Meet the Gorillas and the Polar Bears

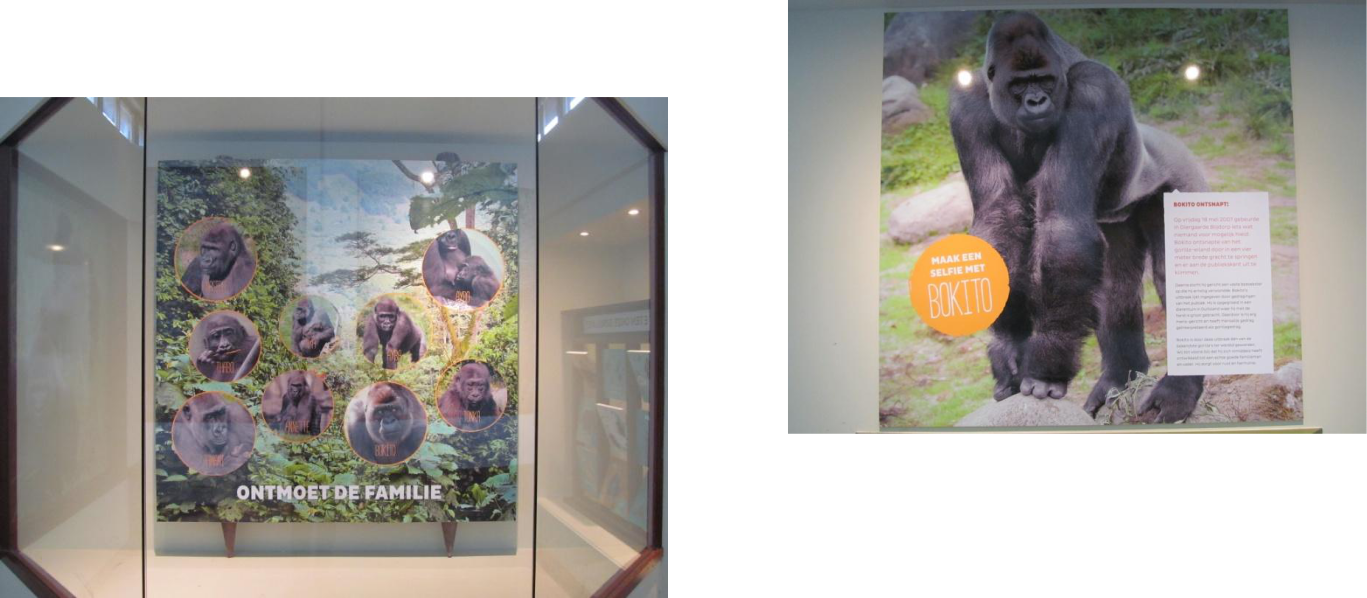

However, at least one visitor shared my thoughts on the artificiality on one of the public cages. As I was staring at the silver back of the famous Gorilla Bokito (figure 4), a little boy (two or three years old) told his mother; ‘Look Mum, the cage is a prison!’ The Gorillas are imprisoned!’ Unfortunately, the mother of the child never gave any reply to the child’s outburst but somewhat embarrassed, took him along to what the boy may deem to be the next ‘animal prison’. Surrounding the Gorilla cage were signs, prohibiting the public to seek contact with the animals and encouraging them to ‘Let gorillas be gorillas!’(figure 5) There were cameras in the building to ensure that people would not tap the glass or flash with their cameras. As can also be seen in figure 4, half of the glass of the largest part of the cage was blinded so that seeing only went in one direction: we can look at the gorillas but they cannot look at us. In a similar way, in the outdoor quarters one cannot come up too close to the Gorillas. As mentioned in the historical overview, where used to be a ditch to separate the gorillas from the public is now a high glass wall. Discouraging direct contact, the zoo does employ other means to bring the gorilla closer to the public (figure 5 and 6). Figure 5 is a picture of all the members of the group with the slogan ‘meet the family’! Furthermore, every gorilla had its own sign, describing their essential characteristics and behavior (figure 7). The message of the setting of the cage and the signs that surround it seems to be then to watch the animals from a distance without disturbing them. The whole family notion and what characterizes the gorllias as a group is futher elaborated upon in Blijdorp’s website.

Figure 4 and 5.

Figure 6 and 7.

Something altogether different seems to be going on in the presentation of the cage of the polar bears. No sign informs the visitor not to flash or let ‘the polar bears be polar bears’. On the contrary: the zoo has gained publicity due to apparent ‘games’ that are played between visitors and the polar bear twin (born in 2010) and pretty pictures of polar bears staring through the glass with the slogan ‘nose to nose with the polar bears: do you dare?!’ are shown on the website. Indeed, I was part of a large crowd of people looking at one of the polar bears who was constantly jumping up and biting in something what appeared to be small rubber buttons, placed just above the glass. I was wondering whether to interpret his behavior as playing and I felt rather uncomfortable because of it. Among the little children that were standing close to the glass one burst out in tears, telling her parents she was scared and wanted to leave. At the other end of the cage we saw a second polar bear, who was constantly pacing from the one side of the cage to the other. How I experienced watching these polar bears was the entire opposite of what I was promised to see and feel upon reading the Blijdorp’s website. On the website every animal has its own ‘passport’ that describes the characteristics of the specific animal in the wild and elaborates on their lives at the zoo. Interestingly in the passport of the polar bear, it is emphasized that a polar bear should not be pacing at the zoo, explaining pacing as a sign of boredom and possibly unhappiness. In order to counter such boredom, the zoo throws in ice blocks with fish and adds various equipment to play with. I could not find the play-equipment or the ball the bears play with in one of the video clips shown on the website.

Of course I cannot assume that the visitors present had all read or scanned through the website and should have seen the disconnect between what was presented there and in the zoo itself. What did made me wonder tough was that no-one seemed to be appalled by the sight of the pacing and endless jumping of the polar bears. The visitors were stuck to the glass, caught in what seemed to be an intense staring.

Concluding Reflections: A willing suspension of disbelief?

John Berger argued that ‘the zoo cannot but disappoint’ […]the public purpose of zoos is to offer visitors the opportunity of looking at animals. Yet nowhere in a zoo can a stranger encounter the look of an animal. At most, the animals gaze flickers and passes on. (Berger, 28). Central to Berger’s argument is that animals have disappeared. We have replaced the animal with an anthropomorphic image and turned it into a product for our own entertainment, leading not only to an immense marginalization of animals themselves but also an irreplaceable loss to our culture. The respectful attitude that used to be central to our relationship with animals, a stance from which our looking at them could inform and teach us things about them and ourselves cannot be recovered.

After my visit to Blijdorp I however wondered to what extent Berger assigns too much of a curiosity and inquisitiveness to the visitor. In general, the zoo-goers I encountered at Blijdorp did not seem to be that interested in particular behavior the animals display nor to what extent their cage is natural or artificial. It made me wonder whether the visitors were looking good enough to be disappointed. Many critics have pointed out how the zoo aims to succeed in providing such an immersion but have failed to notice that immersion is also dependent on a willingness on the side of the visitor. It asks a certain attitude that I think can best be described as ‘a willing suspension of disbelief’. The notion was coined in 1817 by the poet and philosopher Samual Taylor Coleridge. He thought that if the writer was able to convey a semblance of truth in a supernatural or fantastical tale, the reader would temporarily suspend his judgment concerning its unbelievably;

- my endeavours should be directed to persons and characters supernatural, or at least romantic; yet so as to transfer from our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith. (Coleridge, chapter XIV)

The zoo presents us with a story that narrates about happy animals, families we can look at and observe, bears that want to play with us through the glass. For a day or a couple of hours we imagine ourselves to be wandering through the various different continents. We are willing to overlook the artificiality of certain cages, to look away from wandering visitors and animal behavior that may indicate boredom and unhappiness. We want to believe in the story of special encounters and willingly close our eyes to everything that may reveal it as fiction. It would go beyond this paper to think about the ideas and possible dimensions of the story of the zoo, but I believe there is much more to discover in this field.

There is a danger in immersing oneself in the story the zoo presents one with, as I already hinted at earlier. Whereas in reading novels the suspension of disbelief usually helps the reader to discover truth and beauty in the imaginary, in the case of the zoo it distract us from what may really be going on. Bradshaw et al. argue that seeing involves objectification and possession and they attempt to show that if we want to bring the animal back from extinction we have to abandon our presumption of what they characterize as ‘right to sight’. Having the animal on display for our own leisure or education cannot allow for genuine interaction but renders them ‘into silent, disempowered objects robbed of agency and autonomy. (Bradshaw et al. 152). They argue for a different kind of approach towards animals that focuses on interaction. ‘The privilege of seeing and watching one another is attainable only through mutual consent and sustained time together, getting to know each other for the purpose of living well together. According to them then, the zoo is most definitely not a place that allows for’ special encounters’.

To conclude, the zoo brings the animals close to the visitor but through stories that do not connect to the zoos everyday reality. Wanting to have an entertaining and enjoyable visit, visitors do not seem to look at factors that may subvert the zoos’ story about happy Gorilla families, contact seeking bears and large cages. Yet the factors that indicate another sadder story are not well-hidden. Berger argued that the zoo cannot but disappoint, but it only disappoints when you choose to look at that which subverts the zoos’ story.

Bibliography

“Beleidsplan Diergaarde Blijdorp.” Diergaarde Blijdorp, Dec. 2013, www.diergaardeblijdorp.nl/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Beleidsplan-Diergaarde-Blijdorp-v12-2013.pdf. Accessed 6 Apr. 2017.

Berger, John. “Why Look at Animals?” In Why Look at Animals. Penguing Books,2009, pp. 3-28.

“Bokito blijft voorlopig binnen.” NOS journaal, Webarchive, April, 2007 http://web.archive.org/web/20090207074818/http://nos.nl/nosjournaal/artikelen/2007/5/ 19/190507_bokito_blijdorp.html. Accessed 6 Apr. 2017.

Bradshaw, G. A. et al. “Open Door Policy: Humanity’s Relinquishment of “Right to Sight” and the Emergence of Feral Culture.” In Metamorphoses of the Zoo, Animal Encounter after Noah, edited by Ralph R. Acompora. Lexington Books, 2010, pp. 151-166

Braverman, Irus. Zooland: The Institution of Captivity. Stanford University Press, 2013.

Coleridge, Samual, Taylor. Biographia Literaria. Project Gutenberg.

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/6081/6081-h/6081-h.htm Accessed 8 Apr. 2017

Geertz, Clifford. “Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture”. In The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays. Basic Books, 1973, pp. 3-30

Salih, Sara. “The Animal You See.” Interventions vol 16, no. 3, 2014, pp. 299-324.